Example Number One:

Example Number One:

P. J. Collins

Sam Tanenhaus

Buckley: the Life and the Revolution

that Changed America

New York: Random House. 2025

This month the Postal Service issues a new “Forever” stamp honoring William F. Buckley, Jr. (1925-2008). Its portrait is distinguished by a) being black-and-white, like a photograph, and b) not looking an awful lot like the gentleman in question.

One wonders why the art director bothered with engaging a professional illustrator to reimagine Mr. Buckley, a figure with whom they are evidently unfamiliar. Why not simply take a familiar photograph (perhaps from a book cover of collected essays, e.g., The Jeweler’s Eye or The Governor Listeth) and just punch it up a little in Photoshop?

I find something of the opposite problem in Sam Tanenhaus’s recent biography, Buckley: The Life and the Revolution, etc. We get an abundance of actual images and vignettes, in photos and prose, each recognizable; yet a clear portrait of the man fails to resolve itself in the biography as a whole. Daunted by the sheer mass of the book (1040 pages) I went straight to the index, early on, checking to see which names got a lot of ink, and which ones got passed over. The results didn’t clarify the picture entirely, but they helped show me where the story was spotty and incomplete. I’ll talk about some of those holes farther down.

The book is sprawling and episodic. An easy read, for the most part, but lacking the soaring and tense plot arc we got in Tanenhaus’s biography of Whittaker Chambers.[1] That was the book Christopher Buckley was thinking of when, after his father’s funeral, he asked Tanenhaus to consider taking on an authoritative life story of William F. Buckley, Jr. That seemed a good choice: the Chambers book is a superb narrative, stuffed full of Sturm und Drang, with lots of personal agony and slow, grueling vindication. A heroic romance along the lines of The Count of Monte Cristo, only with real-life historical gravitas as well. When Tanenhaus was writing the Chambers book in the early 1990s, Alger Hiss was still very much alive, and to some extent so was the Hiss-Chambers case. It wasn’t hard to find people who had devoted years to proving Alger’s innocence. I knew people like this. They told me they still talked to Alger. Even in 1990 they would grab you like the Ancient Mariner and tell you insistently, with bulging eyes, how they had collected acres of evidence back in the 1950s, and it was now proven, beyond the shadow of a doubt, that the FBI could and did construct a fake typewriter!

Alas, Tanenhaus could not frame the Buckley story with a similarly compelling plot and moral, let alone with frothing crazies full of inchoate rage a half-century on. This hero isn’t thrown into a dank prison for fourteen years, or threatened with extinction during the Stalinist purges of the 1930s.The closest Bill Buckley ever came to being an outcast was when he was barred from giving an Alumni Day speech at Yale because it was too critical of faculty and administration. Explaining who he is or what he and his National Review stood for (once upon a time) is no easy task when the historical context or the 1950s and 60s has long vanished. You’d have to scratch hard through old bound volumes and collected essays to find anything both interesting and conceivably controversial.[2]

But Tanenhaus does his best, making it the story of Buckley’s thirty-year struggle against liberal and complacent politicians and opinion-makers, ending with the triumphant election of Ronald W. Reagan as President in 1980. Here is young William F. Buckley, Jr., resolutely fighting his uphill battle to make “conservatism” acceptable and even fashionable. There he goes, politely shunning the cranks of the “fever-swamp right”. He tactfully praises members of the John Birch Society while calling its founder (who contributed $2000 startup money to National Review) a loon. We see Bill Buckley supporting segregation when that seems a winning cause in the mid-50s, then quietly stepping away, leaving James Jackson Kilpatrick of Richmond as the last syndicated columnist to man that crumbling fort. Buckley cheerfully rides through the Goldwater loss in 1964, and then makes his own amusing run for New York mayor the following year. Two years later he’s a known television personality and makes the cover of Time, in a spindly David Levine caricature (“Conservatism Can Be Fun”). Through it all, he manfully puts up with those Republican Party opportunists who gave us the insipid Eisenhower and deceitful Nixon, and even attempted vainly to push William Scranton and Nelson Rockefeller. And in the end, unbowed and barely battered, Buckley and his little magazine succeed in achieving the near-impossible: Ronald Reagan is elected President in 1980. It’s a victory Reagan generously if glibly credits to his favorite reading material, Bill Buckley’s National Review.

And so at last, parade’s end. The climax of the story. If the triumph seems limp and unremarkable today, just put it down to foggy hindsight, and maybe politics-fatigue. Anyway, it was such an innocent time back then, was it not? We were so easily impressed. And, truly, Reagan didn’t really accomplish much, did he? A wasted presidency, some say today. “A historic failure of nerve,” carp the critics. “To True Believers, Reagan’s presidency was like an eight-year Inaugural Ball.”[3]

Surely that presidency was instrumental in bringing the fall of the Soviet Union and the collapse of the Iron Curtain. But that’s a hard story to get across today. Just saying it, you feel like George W. Bush hanging his “Mission Accomplished” banner, thirty days into his endless Iraq fiasco. Memories fade. Who now recalls Yuri Andropov, the career KGB hood who sent Soviet tanks into Budapest in 1956 and Prague in 1968, and in 1983 was insisting to the world that Reagan, the trigger-happy cowboy, was bringing us to the brink of nuclear war by putting Pershing II missiles in West Germany? Or that nuclear-disarmament propaganda we were continually force-fed, with horrifying scenarios laid out in tedious New Yorker essays, comic books and pop songs about “Nuclear Winter” and “How the World Ends”? And who could possibly give a damn that one of the Reagan Administration’s first priorities was rebuilding the morale and effectiveness of the CIA, after the despoilation of the Carter years?

Weirdly enough, this Collapse of Communism occurs offstage even in Tanenhaus’s Buckley, with scarcely a footnote. (Mikhail Gorbachev barely makes it into the book’s index; Boris Yeltsin not at all.) Thus the peak of Buckley’s career, and National Review‘s, comes as a sad-trombone anticlimax. Maybe the chopping block is to blame: I imagine pages of toothy geopolitical analysis about the 1980s-90s winding up on the writing-room floor, as the author cuts his unwieldy typescript down to publishable size.

But probably not. The geopolitics aren’t there because Sam Tanenhaus just isn’t a geopolitical kind of guy. His métier is writing about individuals and personal crises. One reason his Whittaker Chambers works better than Chambers’s own memoir, Witness, is that it leaves out all the Chambers-ian brooding and thumbsucking, about Historical Necessity and the Crisis of the Middle Class. The kind of thing that makes my eyes glaze over, as Bill Safire used to say. And for most readers it’s not nearly as interesting and down-to-earth as stuff like Bill Buckley’s slide into near-bankruptcy in the 1970s. That was the result of overleveraged and unprofitable side businesses (Starr Broadcasting Group radio stations) as well as heavy personal debt—largely from the purchase and upkeep of yachts—which Bill would take on compulsively. And I must say, Tanenhaus really does indulge his Schadenfreude over financial setbacks of Buckley and kin. He loves giving us the bad news, at ungainly length and in considerable detail. We get continuing updates on the downturn of the family’s oil business and the eventual sell-off of their gigantic estates in South Carolina and Connecticut. And all the lowdown about the alcoholism and various mental illnesses and physical disabilities that eventually befall many Buckleys and in-laws.

Anyway, once we get Reagan safely in the White House, Sam Tanenhaus seems to be in a hurry to wrap things up. Perhaps he’s been on the job for 14 or 15 years, and Random House now wants him to get them a semi-final typescript so they can have the book out for Buckley’s centenary in 2025. And so Sam skates through Bill Buckley’s last couple of decades…in about 20 pages. Not much to say here, besides valedictions and physical decline. There’s the death of wife Pat, his lookalike partner and alter ego, in 2007. Then Bill’s prescription-drug gulping, suicidal thoughts, and his quick and merciful death the following year, in his garage office. Finally, a memorial mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, with some words from Henry Kissinger (a longtime chum) and a supercilious eulogy delivered by his apostate son, Christopher. That’s all, folks!

* * *

And so now we move on to the index, that dark, revelatory underbelly where we find who’s been put in and who’s been left out of the story Tanenhaus and company want to tell us. After 15 years of research, writing, interviewing, and re-fact-checking, the book must have first emerged as a draft twice the size of the present doorstop. Great hunks of material had to be excised. Maybe they concerned minor figures who only briefly intersected with the Bill Buckley career trajectory. Or they were personalities in some of the painfully protracted lawsuits that Bill dragged on for years in the 1970s and 80s. Or they were colorful anecdotes that were thought a bit too unsavory, in the opinion of Tanenhaus or another party (most probably Chris Buckley, his quasi-patron).

As an example of the last I think in particular of an event that appeared in John P. Judis’s 1988 biography of Buckley[4], on which Tanenhaus often leans. It is 1975, and Bill and son Chris and other crew members of Bill’s yacht Cyrano have docked in the Bahamas, preparatory to sailing across the Atlantic to Marbella. (This is the voyage Bill wrote about in the memoir Airborne.) Surprising them on the dock is none other than Bill’s old friend Roy Cohn, wearing a bikini bottom and a t-shirt that says SUPER JEW. Roy has a muscled young man with him, whom Chris guesses to be a rough-trade pickup. The Buckleys and crew huddle and deliberate at length: “How can we avoid having dinner with those two?”

That story does not appear in the Tanenhaus bio, though there is plenty of Roy Cohn elsewhere in the book, particularly back during the McCarthy era. With Tanenhaus, the mid-1970s pass in a storm of financial woes followed by a blessed, steady windfall from bestselling novels. Bill begins to write his Blackford Oakes spy-thriller series (Saving the Queen, Stained Glass) and all is thereafter smooth sailing. There is no room here to discuss the 1975 voyage of the Cyrano, or Roy Cohn’s colorful lifestyle. But Tanenhaus usually finds plenty of time and space to talk about men who may or may not be light in the loafers. Apropos of nothing, he suddenly informs us that National Review publisher Bill Rusher was gay (a longstanding rumor, true or not); and tells us how NR editor Marvin Liebman, never firmly closeted anyway, publicly outed himself toward the end, after Bill proposed that HIV+ gay men get themselves tattooed prominently with that useful disclosure.[5] And of course he tells us about the number of gay men in the Buckley’s social circle (not to be unexpected, given that Pat Buckley was society’s top A-lister); and reminds us of how Gore Vidal would continually insinuate that Bill was a closet queer. Finally he asks Bill’s old school friend from the Millbrook Academy, Alistair Horne, if Bill had ever showed any predilections that way. (No, not at all; repelled by the idea.) I’m surprised nosy-parker Tanenhaus didn’t cast any aspersions on son Chris—though of course if he did, they surely wouldn’t show up in the published edition.

With all this fluttering around, an anecdote about Roy Cohn at dockside with his bikini trunks and rent boy might have seemed a bit excessive. Or it could be Tanenhaus just didn’t like Cohn’s t-shirt.

But as to the index; I was going to talk about the index, wasn’t I? My first port-of-call in the index was Professor Revilo P. Oliver (or RPO, as we say). I’d known for years, via connections of the first degree, that RPO was a treasured old family friend, one whose cordial allegiance survived his departure, early 1960s, from the masthead of the National Review magazine.[6]

But I had a specific question about RPO that is trivial and playful: was he or was he not Best Man at Bill Buckley’s wedding? Ancient history here: it’s July 6, 1950, and Bill weds the wealthy, regal, immensely tall Patricia Aylden Austin Taylor in Vancouver BC, in what is said to be the largest (outdoor) wedding ever staged in that part of the world. Now, I’d heard and read this “best man” factoid a few times. It’s been attributed to, or blamed on, Paul Gottfried, but no one’s ever nailed it down. The story seems plausible enough on its face. Long before National Review was launched, with Prof. Oliver as one of its “conservative” leading lights, he had been a close friend of Buckley’s Yale mentor and friend, Prof. Willmoore Kendall. The two profs been grad students in the early 1930s at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. So Prof. Kendall would almost certainly be at the wedding. And RPO too? Well, I can’t find it documented in writing. But tantalizingly, in a home movie of the event, one can spot a large gentleman with slicked-back black hair and mustache—the only visible mustache in this 1950 crowd.[7]

Prof. Oliver here, if indeed it is he, would be just turning 42, and looks rather like a taller, younger, jollier version of Louis Calhern, the movie actor. (Whom you undoubtedly remember from one of that year’s finest motion pictures, The Asphalt Jungle.)

Buckley wedding, July 1950.

However I can now confirm, with a modicum of confidence, that RPO was not Bill Buckley’s best man. At least not according to the marriage notices prominently placed in the New York Herald Tribune and the New York Times the following day, July 7, 1950. Under the slugline “Special to the New York Times” (newspaperese for “an outsider wrote this one”), we read that Buckley’s best man was in fact elder brother James L. Buckley, who later was U.S. Senator from New York, 1971-1977. The many ushers include Bill’s two other brothers and some brothers-in-law, including college chum and sometime writing colleague (McCarthy and His Enemies) L. Brent Bozell. There’s also that prep-school roommate and future bestselling author Alistair (aka “Allan”) Horne. Then we have all the bride’s sisters, friends, in-laws counted among Pat’s attendants. Just listing these names in the wedding party takes up over three inches of column space. But nowhere do we see the names of Professors Revilo P. Oliver or Willmoore Kendall. No matter; as a rule, only family and members of the official wedding party, get listed in these newspaper notices.

In the end we have several possibilities: a) RPO wasn’t there at all, therefore he’s not Mustache Man or Best Man. b) But perhaps he was at the wedding, and stood in for Jim Buckley because of some last-minute problem. Perhaps Jim was ill, or missed his flight; and so, come wedding morn, hopeful eyes turned to Prof. Kendall as a backup, but Kendall too was nowhere in sight. And so, RPO gladly stood in, and the “Best Man” story got carried forth via oral tradition (never mind what the wedding notice said). Unfortunately all the principals are now dead and I cannot ring one of them up and ask. So finally, we are left with my own safe guess: c) Mustache Man is indeed RPO, but he wasn’t best man; that’s just some old rumor that’s been kicking around.

As it happens, there is no discussion of this “Best Man” question in the Tanenhaus book. In fact there is almost no mention of RPO at all. In passing he’s called an “NR contributor…friend of Willmoore Kendall, and a fanatical racist and anti-Semite” (p. 363, Kindle edition). That’s ungenerous, and smacks of incuriosity. John P. Judis had a lot more to say about RPO in his 1988 Buckley biography. But RPO was still alive then, and harder to ignore or lose down the memory hole. So, snip-snip, sayonara, RPO!

Considering other notorious scamps from the early NR days who might have been blue-penciled to near-nothingness, I lighted upon George Lincoln Rockwell. And wouldn’t you know it, he’s gone missing entirely. His name appears once, as a slur, when Edward Bennett Williams[8] gives a college speech and calls Buckley “the Ivy League George Lincoln Rockwell.” Buckley threatened to sue Williams over that. It was a dumb thing to say, not only because cheap and nasty, but because the real Ivy League George Lincoln Rockwell was none other than that selfsame Brown University alumnus, George Lincoln Rockwell. (Edward Bennett Williams, it must be said, went to Holy Cross.)

Rockwell, a sometime ad man and magazine publisher, was briefly hired by Buckley in NR‘s early days to develop a subscription-marketing campaign aimed at college and university students. Afterwards the two men corresponded occasionally, with snipes and insults. Buckley dismissed Rockwell’s new American Nazi Party kick as mental derangement. Finally, rather unctuously, he sent over a priest-psychologist to talk to Commander Rockwell and see if Rockwell could be talked down from his “mania.” Answer: no.[9]

This missing Rockwell in the index leads us, free-associatively, to another omission that must be deliberate: Willis A. Carto. In the early days of Carto’s Liberty Lobby (late 1950s), he and Buckley maintained cordial, if distant, relations; much as Buckley remained friendly with members of the John Birch Society (for which Carto himself worked for about a year). But they inevitably became enemies, occupying as they did two polarities of the Right-wing universe: Buckley the prudent sailor, tacking close to the winds of bien-pensant opinion, vs. Carto the publisher-explorer of farther shores, contemptuous of “respectable” opinion and prospecting for paydirt among the “kooks.” As though to spite Buckley, in the 1960s Carto acquired the American Mercury, the occasionally racialist and Jew-critical magazine that Buckley ordered NR writers to keep away from in the 1950s.

Buckley himself almost never mentioned Carto in print. But in September 1971, NR published a takedown of him and his various publishing and lobbying operations.[10] Following that, Buckley and Carto spitballed at each other for many years in petty, pointless libel suits, usually leading to nominal damage awards. In the most prolonged of these, a 14-year action decided in 1985, Buckley sued Liberty Lobby for claiming (in The Spotlight newspaper) that Rockwell and Buckley had had a “close working relationship” in the early days of Buckley’s magazine. The court eventually found for Buckley (the “working relationship” wasn’t that close), awarding token damages. Another suit against Carto appeared to be a proxy action spurred by Buckley. An ex-spook who worked for Carto claimed in The Spotlight that Buckley’s old CIA friend E. Howard Hunt, the “Watergate Burglar,” was involved in the assassination of President Kennedy in 1963. The Spotlight even ran the famous photo of Hunt (or his lookalike), dressed as a tramp in Dallas on assassination day. Hunt is unlikely to have seen this article on his own, so presumably Buckley encouraged him to file suit. Which Hunt did, but without success.

* * *

From the early 1960s onward Buckley was easily goaded to sue, generally on account of casual insults, libels and calumnies that would be tossed off in print or on television, and just as easily forgotten in a week if he didn’t draw attention to them. As a public figure who courted controversy, he should have gained a thicker skin as time went on. Instead the opposite happened. Initially his anger and litigiousness were mostly piqued by attacks upon his family, uttered on TV chat shows. From the very beginning, Gore Vidal was the main provocateur, but Buckley was persuaded to keep his powder dry—no defamation suits today, please. They sparred via Jack Paar, David Susskind, the 1964 Convention coverage. Things finally came to a head in their fourth or fifth set of encounters, in 1968, during the Democrat Convention in Chicago. They had been engaged to give commentary, and maybe debate a little, for ABC News, with Howard K. Smith as moderator. Toward the end of the run, Vidal called Buckley a crypto-Nazi, and Buckley called Vidal a queer. It should have stopped there, but they followed up the following year in the pages of Esquire. At extraordinary length, maybe 9500 words, Buckley excoriated Vidal for his continuing and gratuitous attacks on the Buckley family, and slammed him for his apparent delight in perversity and pornographic writing, ending his essay with a perfunctory apology to Vidal for calling him a queer on live television.

In response, Vidal carted out some heavy, if dubious, ammunition. Among the acquaintances who’d told him tales of the Buckley family were the two daughters of the Episcopal minister in Sharon, Connecticut, the Rev. Francis Cotter. These two Cotter daughters both became actresses and television personalities, under the names Audrey and Jayne Meadows. Jayne Meadows married perennial TV host, comic and songwriter Steve Allen. They had a wide circle of friends in the 1950s and 60s, including young Gore Vidal, then living nearby in the Hudson Valley; and the Buckleys as well. This social circle is the real background to the Vidal-Buckley feud. Vidal was a kind of interloper, repeating hearsay: a gossip-queen. The Cotter girls, though, had skin in the game. They’d known the Buckleys since forever, and when they talked about them they saw it as just neighborly teasing. Jayne in particular liked to tell and retell a colorful tale from 1944. One Saturday night in May, it seems, three of the Buckley girls and two of their friends committed a few minor vandalisms at their father’s Christ Episcopal Church (honey and oatmeal in the pews, Varga Girl pinups and salacious Peter Arno cartoons from The New Yorker in the hymnals and prayer books). Bill wasn’t there, he was in South Carolina. He learned about the mischief when he came back to Sharon and learned his sisters had been charged with vandalism and now were awaiting their trial date. The Buckley girls’ motivation was unclear; they had no real motivation; it was a prank. But Vidal, in his Esquire piece, implied that Bill was a party to the shenanigans, and painted the vandalism as dark retaliation against Mrs. Cotter, a real estate agent who’d recently sold a house to a Jewish couple. (That bit may or may not be true, and anyway did not figure in the court case, which ended with a fine. But the story spread far and wide, and mutated wildly over the years. I remember a Jewish acquaintance in college in the 1970s, informing me that the Buckley family had once vandalized a synagogue.)

This speculative anecdote was the only one Vidal related in his article. (His investigative research consisted of the initial news report in the weekly Lakeville Journal, talking about church vandalism.) But there was another old Buckley tale he did not repeat, perhaps because it didn’t manage to find its way into the newspapers or courtroom. That was when, in the summer of 1937, the first two Buckley boys, along with the first two Buckley sisters and local friends, built a wooden cross and lit it on a hillside in front of a resort hotel frequented by Jews. Bill was not present at that event, either, being only 11, and too young to participate in such hijinks. (“I wept tears of frustration,” he wrote in 1992, over missing out on this “great lark.”)[11]

In publishing the Vidal riposte, Esquire broke an agreement it had made with both Vidal and Buckley: that each would be able to read and blue-pencil the other’s essay. Esquire failed to send a copy of Vidal’s draft to Buckley, thereby leaving the innuendoes about the Buckley family unchallenged and actionable.

Predictably, Esquire eventually settled with Buckley, paying at least his legal costs, while Vidal dropped his suit. Tanenhaus does not give the details, but I seem to recall that Esquire made additional payments in kind, by buying years of display ads in National Review, and simultaneously running subscription ads for NR in Esquire. There were also some big Esquire subscription ad buys around this time (1974) in the Yale Daily News Magazine, of which Christopher Buckley was an editor. (A monthly periodical, not a weekend supplement, as Tanenhaus seems to think.)

As a rule, Tanenhaus does not give us details about personality conflicts and lawsuits, and this is bound to result in a lot of headscratching. I was not an NR reader in the 1980s and 90s, so heard about the simmering Joe Sobran problem long after the fact. From what I can learn from Tanenhaus and elsewhere, Sobran was a columnist and then senior editor on the magazine, regarded there as a disorganized, passionate, but often brilliant essayist. In 1993 he was summarily fired from NR after making some remarks critical of Israel and/or Jews in another periodical.

I still don’t really know what the fuss was about, but I’m pleased to say that Tanenhaus succinctly tells us why Sobran was fired. Buckley did it, he said, to make Norman Podhoretz happy.

Buckley claimed to be personally fond of Joe Sobran. And while you wouldn’t guess this from its title, his In Search of Anti-Semitism (1992), seems to have been intended as both defense and constructive critique of Sobran (as well as Pat Buchanan and other, lesser targets). It’s a kind of open letter addressed to NR readers but also The New Republic‘s Marty Peretz, and Commentary editor Norman Podhoretz and Norman’s wife Midge Decter. Midge in particular had complained to Buckley about Sobran incessantly. But of course, there are some subjects you cannot write about, however honestly or obsequiously, without making some parties unhappy. And certain types of folks you can’t ever please anyway. In this case, everyone was unhappy, and Buckley’s book (which began as a long cover essay in NR) looked, and still looks (to me) like a desperate, preposterous venture.

There is an obsessiveness and repetitiveness in the Anti-Semitism book that characterizes much of Buckley’s later non-fiction writing. You see it in the pendulous, overwritten 1969 “On Experiencing Gore Vidal” in Esquire. And it’s noticeable in the drop-off in quality in “On The Right,” Buckley’s thrice-weekly syndicated column, a decline that seems to have commenced around the same time.

Once upon a time, perhaps because I’d idly mentioned that I’d found his father’s recent columns difficult to get through, Chris said to me, “Do you find that he’s become very parliamentarian?” I had no idea what he meant by that. Many years later I suspect that what Chris was really trying to say was something like orotund, talking (writing) like a bloviating orator. Around this time I had a theory about it all: the problem was that Bill was now regularly dosing himself with Ritalin, which he told Chris was prescribed for him “for low blood pressure.” Now, Ritalin has an effect similar to amphetamines. It may give you a boost to write passionately and creatively if you’re doing something like fiction, but in my experience it gives me a passionate need to rewrite every sentence about ten times (if it’s supposed to be polished, expository writing).

Tanenhaus informs us that Bill actually began taking Ritalin in 1958. This I find hard to believe, since not only does that make him a very early adopter (it only went on the market in 1957), but it destroys my whole theory about the decline in quality of his essays just before he became a manic writer of memoirs and those page-turner spy novels: thrillers he supposedly cranked out in three or four weeks while on vacation in Gstaad.

But perhaps I’m not far wrong, and the truth is simply that Bill took a lot more Ritalin as the years passed. Christopher wrote of his father’s last days, when half-empty blister packs littered the night table, and it appeared that Bill was gobbling sleeping pills and “Rits” together when he went to bed. In his final months Bill did not seem to “get it” that Ritalin was a stimulant. I have yet to read a single Buckley thriller, but if ever I open one and it’s phamaceutically enhanced, I think I’ll spot the Ritalin right away.

Notes

[1] Sam Tanenhaus, Whittaker Chambers. 1996.

[2] There is a “Yale Alumni” Facebook group, evidently populated mostly by recent grad students. Recently, after the postage stamps were announced, a number of them were denouncing Buckley in chorus, because they had learned that back in 1957 he wrote an essay, “Why the South Must Prevail,” which argued that negroes, for the most part, were not yet advanced enough to be awarded the voting franchise by fiat. Of course none of these could remember the era or could even fathom that this opinion was fairly mainstream, let alone quite reasonable.

[3] F. Roger Devlin said this once, in 2016, supposedly quoting Joe Sobran; but I have never located the original.

[4] John P. Judis, William F. Buckley, Jr., Patron Saint of the Conservatives. 1988.

[5] This passage about the management of Young Americans for Freedom is particularly choice: “[Bill] entrusted YAF management to Marvin Liebman and Bill Rusher. Both were delighted to be in charge—not least because both were gay and never happier than when in the presence of young men.” Like most of the principals in this tale, Liebman and Rusher were safely dead long before this book made it to galleys.

[6] Prof. Oliver was a founding member, spokesman and writer for the John Birch Society, 1958-1966, a period when editor William F. Buckley, Jr. politely eased his way from what he considered Right-wing and libertarian “crank” groups, including among others the JBS, Liberty Lobby, Ayn Rand’s Objectivists, and Russell Maguire’s American Mercury magazine.

[7] A clip appeared most recently in the 2024 PBS documentary, The Incomparable Mr. Buckley.

[8] Williams was a celebrity lawyer whose clients included mob bosses and flamboyant Harlem congressman Adam Clayton Powell. For a year or so in the late 1950s, Buckley and NR were obsessed with Powell.

[9] Buckley disclosed this long acquaintance after Rockwell’s 1967 assassination, in a column collected in The Jeweler’s Eye (1969).

[10] Bylined C. A. Simonds (Chris Simonds, a rock-music writer whom Buckley had brought over to his magazine to celebrate and comment upon youth culture), the article covered far more detail than even an intrepid young investigative reporter could dig up on his own. It was clearly assembled from dirt files that some helpful outside agencies had available.

[11] Buckley wrote this near the beginning of In Search of Anti-Semitism (1992) a collection of essay-memoirs about how he juggled relations with such annoying people as neocon Jews Norman Podhoretz and Marty Peretz on the one hand, and prickly National Review staffer Joe Sobran on the other. The story about cross-burning had been published at least once before, in John B. Judis’s William F. Buckley, Jr., Patron Saint of the Conservatives (1988). I first heard the cross-burning story myself about 50 years ago, from one of the participants, a friend and neighbor of the Buckleys, and father of some friends of mine. He described vividly that foggy night 40 years before, the wet grass and slippery hillside near the hotel, along with his own weepy regret that he’d come along on this crazy trip. “Oh no, Johnny and Jimmy, don’t do this, let’s go back,” he cried. Or at least he claimed to have cried, recounting it for me long afterward. I gathered this adventure took place in the Berkshires, perhaps over the Massachusetts line. In his 1988 book, John Judis said it happened in Salisbury, in northwest Connecticut. Tanenhaus says it happened in Amenia, New York, two-and-a-half miles west of Sharon, practically in the Buckleys’ backyard. Of course it might have happened in both places, and maybe others. Or it might just be one tall tale that they’d been a-tellin’ since ’bout 1937. Regardless, young Billy said he was sad to have missed it.

I’d like to report that this hefty book (480pp but feels more like 840) offers some new findings and insights about the events leading up to the Charlottesville ruckus of August 12, 2017. [1] Which it does. But alas, the author is easily distracted, chasing down so many rabbit-holes she loses control of her material. She spends an entire chapter talking about “racism” in Virginia, which somehow leads her to T.S. Eliot (a “Yankee” from St. Louis and London, who found Virginia still pristine in the 1930s); then Eliot’s comrade Ezra Pound, who boosted such negro poets as Langston Hughes, yet somehow had a thing about the Jews; and then finally Baker caroms off into talking about Eustace Mullins and the Federal Reserve. Yes, seriously! It’s all new to her!

I believe you should assimilate such material before you are 25…or never touch it at all. In her 60s, Baker is far beyond the age of discernment.

But that wasn’t the point I wanted to make. Deborah Baker’s research doesn’t match up with the received narrative she’s trying to push. Repeatedly she comes up with facts that tell us the mainstream narrative was all out of kilter. But instead of giving an honestly revisionist view, Baker tells us the facts, but then forgets them…and recites the official opinion.

To give a few examples. Two weeks before that fatal date, August 12, 2017, the Virginia State Police, Governor Terry McAuliffe, and Mayor Mike Signer were fully apprised that Charlottesville was going to be invaded by gangs of “Antifa” and “black bloc” rioters. This happened at a briefing near Richmond at the Virginia Fusion Center (the intelligence agency of the state police):

Descriptions of anti-fascist tactics predominated, including reports of leftist subversives bringing fentanyl and cans filled with cement, and Antifa stashing caches of bricks in the area around Emancipation Park.[2]

The foreseen danger, then, was from big mobs of Leftist rioters and protestors who were planning to descend on Charlottesville the morning of August 12. The intelligence officers were familiar with many of them, because they were largely the same individuals and groups who had shown up in Washington in January 2017 to disrupt President Trump’s first Inauguration. (#DisruptJ20 was their hashtag.) It was obvious enough what was going to happen.

Later on—once the August 12 shouting and violence were over—Gov. McAuliffe lied through his teeth about the briefing. He told public and press that the Fusion briefing had entirely focused on “armed neo-Nazis and white supremacists.” And by “armed neo-Nazis and white supremacists” he meant the speakers and audience arriving for an event called “Unite the Right.” Which was a confab scheduled for midday August 12, with the objective of protesting against the removal of the Robert E. Lee equestrian statue from Lee Park in downtown Charlottesville. It was a legal gathering. They had a permit and everything.

In other words, McAuliffe was saying that the rioters with Antifa, black bloc, BLM and whatever, were never considered a serious threat. The real danger came from the people who were assembling legally…the ones with a permit…the folks the Leftists hoped to attack.

But forget McAuliffe. Charlottesville Mayor Mike Signer remembered the July 27 Fusion Center briefing very differently. He said the intelligence experts at Fusion Center talked only about violent Antifa. Antifa were going to throw bombs and rocks and worse. The way to manage them (the state police people told Signer, and later the Charlottesville police) was to keep the two groups far apart. You had to cordon off the “Unite the Right” people from the Antifa mobs who were going to attack them. There was no talk about “Unite the Right” people being violent.

Mike Signer had many signal qualities. Tall, handsome and personable, he was the product of Princeton and Berkeley (where he got a PhD in political science), and UVA Law School. But he comes off badly in this book—a strutting, weak-kneed popinjay. And he took a lot of shellacking in the mainstream press. He got blamed for August 12. For not doing something. Or not doing enough. But seriously, “Charlottesville” was scarcely his fault. You see, like many mid-sized cities, Charlottesville has a “city manager” type of government. Mayor Signer was just a figurehead, not an executive. A nice, presentable guy for cutting ribbons and giving Arbor Day speeches, but not much else.

Furthermore he tried too hard: to please everyone, including militant Leftists on the city council and among the town’s rainbow clergy. Signer opposed moving the Robert E. Lee statue from Lee Park (temporarily referred to as “Emancipation Park”). Yet at the same time he also tried to pander to the anti-Lee crowd, telling them he understood their feelings. Signer liked to give long, pompous, orations to city council members, and some of them considered him a windbag, Baker says. The city council really didn’t like him much.

Perhaps the most cringeworthy thing about Signer is that once, in full rhetorical flight, he claimed to be Jewish…only he wasn’t. It seems he had a Jewish stepfather, and now wanted to appropriate that identity. Author Baker says this all came as a big surprise to the local Jews.

But to get back to the story. Signer learned that a thousand or maybe 1500 Antifa types were getting ready to riot in his town, and he didn’t have the authority to evict them. What could he do? He was just the figurehead mayor. So what happened instead? The governor, the execrable and dishonest Terry McAuliffe, called it all off the morning of August 12, declaring an emergency. The local police told the groups they had to disperse, and so they did.

At least the “Unite the Right” people did. Meanwhile the Antifa rioters continued to carry on for a bit, throwing bottles of piss, and blocking motorists who were trying to escape.

One of those motorists was Alex Fields from Ohio, driving down Fourth Street in his black Dodge Challenger. An Antifa mob, with placards and pipes and bats, tried to stop him, whereupon he revved up and tried to blast his way through. And then somehow an obese 32-year-old woman, Heather Heyer, died, because she collided with the vehicle she was trying to block. She died of a blunt-force trauma, or a heart attack, or perhaps both.

Around the same time, a few miles out of town, two state cops crashed while riding their Bell helicopter. It appears they were buzzing motorists on the highway…and perhaps attempting a deep bank while 50 or 100 feet up. (Something you shouldn’t do at that altitude in a helicopter.)

Baker gives us no details on how the state cops died, in their helicopter joyride, and tells us next to nothing about the background of Alex Fields and Heather Heyer. But what could prevail upon someone to join in a violent demonstration on Fourth Street, waving signs and poles and halting traffic? I’m sure it seemed a great social occasion, a big party for Heather Heyer, who held part-time jobs as a waitress and law-firm file clerk, and probably didn’t get invited to many top-drawer affairs.

Alex Fields is a more mystifying creature. Unlike Heather, who was a local, Alex seemingly came out of nowhere. As in Nowhere, Ohio. Where he supposedly had a paraplegic mother and a father who died before Alex was born. (The press persistently referred to Alex as James Alex Fields, Jr., or even just James Fields: making him even more of a cipher than he was to begin with.[3])

A high school teacher has told reporters that Alex was a diagnosed schizophrenic and on daily medication. And apparently our mad Alex came to Charlottesville, drove to Charlottesville in his Challenger, all alone. Alex comes to an event where he knows no one. None of the Unite the Right participants know him. Fortuitously Alex is dressed in the white polo shirt and khaki trousers of the group calling itself Vanguard America. (Gosh, how did that happen?) The Vanguard America folks let him hold a shield and be photographed a few times with them. Although, again, nobody knows him.

When Alex is arrested and mad-swiftly sentenced for life imprisonment for an auto accident, nobody seems to raise the defense that he is diagnosed as mentally ill. And not garden-variety mentally ill, as with a mood disorder, but actually the sufferer of a biochemically based psychosis, schizophrenia.

What’s going on here? Why is Alex Fields (supposedly) in a Federal maximum-security prison in Missouri, rather than in a mental hospital or a prison for the criminally insane? The whole thing makes no sense. I personally doubt this “Alex Fields” person is in any prison, if he exists at all.

In a significant omission, author Baker makes no effort at all to look up and interview Fields. In theory that should be easy to do so. Besides, she might have got a nice Rolling Stone cover out of it. Bigger than Charlie Manson.

Similarly, she makes no effort to interview Jason Kessler (ostensible showrunner for the “Unite the Right” event) or Richard Spencer, or any of the other gadflies and podcasters who were due to speak at his August 12, 2017 confab. Baker gives us a lot of vague commentary from lesbian clergy and stoner activists in Charlottesville, but generally avoids the major figures.

One exception here is an individual who may have been the most central of all, although she’s generally written off as just another Charlottesville weirdo. That is Emily Gorcenski. According to author Baker’s telling, Emily was basically the hub, the linchpin, of the whole Antifa inundation of Charlottesville in August 2017.

I first heard of her through an Identity Evropa friend who on social media was challenging her to a throwdown once he got down to Virginia. I think he posted this note around August 10. The implication was that Emily was leader of the Charlottesville Lefty activists, and much more than that. Since at least May she had been haranguing all the Antifa kingpins to round up their troops and “Come on down!” (As Ed Reimer used to say in the Northeast Airlines commercals.)

And so they did. And the generous amount of ink that Deborah Baker gives Emily Gorcenski is well earned. At least, Emily’s the only interviewee Baker goes into any sort of depth with.

Officially a “data scientist,” who of late has mainly been working and living in Berlin (presumably because of her complicity in the 2017 excitement) Gorcenski has a life story that I found unbelievable on the face of it. Per Baker, she was born of a Polish-American family in the Connecticut River valley of northern Connecticut. She does not look a bit Polish; rather, pure South Chinese, if anything. Thus I assumed, when I first saw her on social media, that she was adopted. You know, like those Korean War Orphans we used to see around. Except Emily is clearly not Korean, and also about thirty years too young to have been a Korean War Orphan.

According to Emily’s story (as related by Baker) when she was twelve years old she was told by her father (her legal “father”; her birth parents were now divorced) that “I am not your real father.” No, the real father was some Oriental that Emily’s mother got it on with. And that’s why Emily did not look like her blond-haired, blue-eyed Balto-Slav brothers and sisters in the Gorcenski family. Emily apparently never questioned any of this before she was 12, and never tried to look up her real father.

The rest of her personal saga is too outré for a family publication such as this, but by August 11, 2017 she was in Charlottesville, strapping on a SIG Sauer 9mm into her waist holster. She tweeted this in photos. This was the night of the “tiki torch march,” an impromptu preliminary event the night before the Unite the Right gathering. 400 or 500 early arrivals—mostly young men, but not a few young women, all in polo shirts and khakis—were parading through town, around the University.

And Emily was armed for bear. She went out to Nameless Park in Charlottesville and joined fifteen or twenty other Lefties holding hands around the statue of Mister Thomas Jefferson. Now Emily livestreamed her experience, showing the tiki torchers parading into the park, circling the statue. It was magnificent choreography—like the Roman legions snaking down the hillside, before the final battle in Spartacus! And Emily rose to the occasion. She wept and screamed and cried into her smartphone as she livestreamed the story. “Where ARE you? Where are the REST of you? Only twenty of us! We are F***ed!”

Notes

[1] A recap, for the young at heart: There were a series of “Alt Right” and identitarian demonstrations in America in early 2017, mainly in New York, Washington, Boston, and Charlottesville. On Mother’s Day, May 2017, a small gathering in Charlottesville, led by Richard Spencer, protested the city council’s intention to move the Robert E. Lee statue out of Lee Park. Activist Jason Kessler proposed a grand, all-inclusive gathering of all Rightist groups in America, to descend upon Charlottesville on August the 12th, the day grouse shooting opens. It was so widely publicized that Leftist activists jumped on it and made it their own. The Rightist gathering itself, Unite the Right, never took place, although there was a torchlight procession the night before. Several deaths were attributed to the protests and riots.

[2] Lee Park, north of downtown, had temporarily been renamed Emancipation Park. The statue of General Lee and Traveller was later removed and melted down. The park is now given the uncontroversial label of Market Street Park. (East Market Street and 1st Street, near the Downtown Mall in Charlottesville.)

[3] At the online journal for which this was originally drafted, the editor mystifyingly changed all my “Alex Fields” mentions to “James Fields.” Some trouble with reading comprehension there. Meantime a couple of obvious typos were ignored.

Fake Nazis, probably Feds and/or Antifa, with backwards-swastika nylon banner and CSA Battle Flags from ye Olde Noveltie Shoppe…freshly unfolded from their cellophane wrappers!

(Being some draft notes for a book review concerning the Antifa riots in Charlottesville, August 12, 2017. The final draft was quite different: less frivolous and self-revelatory. These sections are intelligible, sometimes enjoyable, but increasingly disjointed.)

What I remember most about the days leading up to the big Charlottesville party in August 2017 was that it was all a total joke. It was going to be a laff-a-minute over-the-top free-for-all. A lot of KEK flags waving and kids running around in helmets and tactical gear, while TV news crews sucked their thumbs and went, “What does it all mean?”

This sort of guerrilla theater had been going on for months, in New York and Boston and Washington, and even a little bit here in Cville. Fab fun for fashy larrikins!

A few of us ladies were talking about setting up a big trestle table full of snacks topped with a huge sign: SAMMICHES! After we knocked the idea around a little, I pointed out that the day was probably going to be hot, the sandwiches would go bad, and anyway who wants to stand out in the sun just to be a jokey tableau vivant? Right?

A friend was going to rent one of the ski-lodge condos at nearby Wintergreen Mountain and get some folks to share the expense. It was a big four-bedroom unit that theoretically could sleep 12, or 15 people; you could rent it for a whole week for something like $400. We would party for the whole long weekend: before, after, and maybe even during the “Unite the Right” event. You might be wasted, after all, come the morning of August 12. In that condition would you really want to stand around in a hot park in Charlottesville and listen to some podcaster rant the same bog-obvious truths that everyone in his right mind already agreed about?

In the end we blew the whole thing off. Didn’t go to Wintergreen, or Charlottesville, or even send along a crate of sandwiches. We watched the famous Tiki Torch March on Friday night, August 11. “Unite the Right Eve,” as it were. And found it mighty entertaining. Sometime after 9 p.m. we saw a handful of spindly antifa types encircle the Jefferson statue in Nameless Park, as though to protect it (which made no sense at all; it wasn’t under attack). They were weeping bitter tears and shouting obscenities into their smartphones, because they weren’t as cool and good-looking as these hundreds of guys (and maybe two dozen gals) in their white polo shirts and chinos. These young Adonises and Freyas, were parading with tiki torches they’d purchased that afternoon at the local big-box store. We watched as their double-filed ranks coiled their way around those antifa ragamuffins at the statue. Magnificent choreography—like the Roman legions snaking down the hillside, before the final battle in <em>Spartacus</em>!

Honestly, we didn’t see it coming. A friend in Identity Evropa had been sending angry taunts on social media to a weirdo down in Charlottesville, someone named Emily, who purported to be the main organizer of the “counter-protestors.” That would be the handful of pathetic hippies linking hands around the Jefferson statue. A thousand more would arrive in the morning, along with Federal agents and news crews, all ready to riot and put out the story that they weren’t the culprits, they weren’t the violent mob. No, the guilty ones were those Right-wingers who were planning to convene peacefully in a park at noon. They’d come for an event called “Unite the Right,” which newsmedia and antifa continually referred to as a “rally,” though it was really nothing more than six or ten speeches. In the end it was canceled and didn’t happen at all.

Deborah Baker was born in Charlottesville and grew up a few miles away. So she was personally mystified and intrigued when “Charlottesville” happened. So she did a lot of dogged research, not investigating every nook and cranny and leading personage, but generally sticking to stuff she already knew, and local folks she could easily interview. So unexpectedly she talks a lot about T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, but never gets around to talking to most the big names that came out of the August 12, 2017 ruckus. No Jason Kessler, Richard Spencer, Mayor Mike Signer, Governor Terry McAuliffe. Despite this imbalance I can report that her book gives us new findings, with a reasonably clear itinerary of what happened that day. But—alas! While some useful revelations are there, Baker has difficulty acknowledging them. This is because they don’t fit into the received narrative she feels constrained to follow. It’s the mainstream media narrative, the only one she knew, apparently. The one where some Right-wingers, “white supreemists” and “neo-Nazis” caused all the trouble. Because they were bad people for simply existing, and they wanted to give speeches in a park where they had a permit to gather and speak.

Yet here’s the irony: Baker describes in detail how the violence at Charlottesville came mainly from the mobs of rioting “counter-protesters” who arrived in town that morning. And still she persists in pretending it was all caused the other side, those Right-wingers scheduling a speakers’ platform in a park.

Her misdirection is absurd, but also entertaining. She is like a hostess who spoon-feeds you dogfood out of a Ken-L-Ration can while chattily describing it as vegan energy food, made of low-sodium tofu with all-natural electrolytes and branch-chained amino acids. (“I read all about it in the Atlantic and on BuzzFeed and saw it on CNN.”) The mystery is why she’s bothering to do this. My easy guess is that she just wanted to get her book published, and chose to take the easy route, reciting the received narrative rather than acknowledge what her lyin’ eyes and ears were tellin’ her. Somehow she knew that if she wandered too far off the reservation, she’d never get the book published.

And so her story shows us clearly that the rioting, violence and deaths [1] of August 12, 2017 were mostly the doing of Left-wing activist mobs—a thousand or more individuals—who descended upon downtown Charlottesville that Saturday morning. They intended to cause disruption and violence, and that’s what they did. They threw their molotov cocktails of pee and poo, whacked passing pedestrians and motorists with giant flashlights and lengths of pipe, made instant flame-throwers out of aerosol paint cans and Bic lighters. And all this happened, Baker explains, because some Right-wingers (fascists, nazis, ku kluxers, white supreemists, aunty-seemites, whatever) were planning to assemble in a nearby park for something called “Unite the Right,” a series of speeches, where their major gripe was that the city of Charlottesville wanted to remove an equestrian statue of R. E. Lee from Lee Park. [2]

Baker does a good job of being oblivious to her own cognitive dissonance. She illustrates that paradox George Orwell described when writing about propaganda in wartime: “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” Anyway, she tells a tale in which a sleepy college town endured massive riots leading to countless injuries and at least one “murder,” and it was all because some Right-wingers wanted to protest against the removal of the R. E. Lee equestrian statue in Robert E. Lee Park. Never mind that their scheduled August 12 confab, called “Unite the Right,” never happened (because the governor of Virginia declared an emergency and the police when the riots started). Or that the event would have been little more than a handful of podcasters giving speeches in Lee Park, and the whole thing would be over in an hour or two.

Or that this gathering that never happened was perfectly legal and had a permit from the city. Those are all moot points to Baker. Because at the end of the day, the kind of people who’d dream up a “Unite the Right” speakers’ program (the media always called it a “rally” for some reason) had to be crazy-evil to begin with. They were, or associated with, White Supreemists. Even self-described <em>Nazis</em> and Fascists. Or the kind of people who like to wave the Confederate Battle Flag, which as we all know is a just a dog-whistle symbol for the <em>Klu Kux Kann. Once you’ve identified evil like this, it’s easy to go along with the rest of the program, because horrible happenings deserve harsh remedies.

Her cynical bias is tolerable, so long as Baker is giving us information that seems new or useful, and that happens often enough. For example: Charlottesville has a city-manager type of government, wherein the mayor is little more than a figurehead for cutting ribbons and giving speeches. Such lack of executive ability can be a fatal weakness. The mayor, Mike Signer, couldn’t simply cancel “Unite the Right” on his own say-so, citing public safety and noting the incoming threats from antifa mobs. The event had a valid permit to assemble in Lee Park on August 12, and its organizers successfully fought off attempts to change the venue to a park outside of town. When the Unite the Right even was finally canceled, a half-hour before showtime on Saturday morning, it was through an emergency declaration from the governor, Terry McAuliffe. By that point the damage had been done.

There are some glaring omissions in her research. She talks to city officials and local clergy, as well as activists and rioters. She doesn’t talk to any of the people scheduled to speak at the Unite the Right gathering…

Alas, she lacks the courage or ability to recognize what is in front of her nose, and She tells us in detail how wild-eyed and driven were the Left-wing activists who came together to riot and demonstrate on Saturday August 12, 2017, yet nevertheless persists in blaming the violence of the day on something that never happened: a series of speeches scheduled to take place at noon in Lee Park, north of downtown Charlottesville. As you no doubt recall, the planned event was called “Unite the Right,” the ostensible purpose of which was to protest the removal of a General R. E. Lee equestrian statue from the Park. This Unite the Right gathering, or “rally” as the newsmedia called it for some reason, never took place, for the simple reason it was canceled. The violence and rioting that went on August 12, 2017 were almost entirely due to the thousand or so Left-wing activists—Antifa, anarchists, BLM, however they labeled themselves—who descended on downtown Charlottesville that Saturday morning. Their presence was not random or happenstance. They had been planning this free-for-all outing for a month or two, mainly within their activist clubs and groupuscules in Philadelphia and New york and elsewhere, but they were also also with the urging coordination of a handful of energetic and unhinged

This was The August 12, 2017 Unite the Right “rally” in Charlottesville, an event that never actually happened, as those of us with discerning memories are well aware. It never happened for the simple reason that it was canceled.

The city granted a permit; was pressured into trying to rescind it; found that it couldn’t; tried to persuade the Unite the Right people to transfer their venue from Lee Park (by the University) to the city refused to provide police protection—even though a thousand or more antifa activists and other violent demonstrators descended upon the town on Saturday morning, the 12th. The governor of Virginia declared a state of emergency, with the state police telling any remaining Unite the Right attendees to disperse. The crowds of so-called “counter-protestors” kept rioting and demonstrating all day, however, even though they now had nothing to protest against.

Accordingly, the most indelible news images from that day show the rioters rioting: throwing rocks and bottles of urine or whatnot towards some (usually offscreen) foe. Then there’s the famous scene of the rioters on Fourth Street beating automobiles as their drivers struggle to get out of town.

NOTES

[1] Three deaths are usually ascribed to the Charlottesville riots. Two state policemen crashed their Bell helicopter while buzzing motorists on the outskirts of town. More famously, an obese 32-year-old woman named Heather Heyer was struck by a black Dodge Challenger while she was in a mob on Fourth Street trying to block traffic. She died of cardiac arrest and/or blunt force trauma. Notable among the wounded was 20-year-old black rioter DeAndre Harris, was seriously beaten about the head after attacking a white man with a giant flashlight.

[2] Lee Park, north of downtown, had temporarily been renamed Emancipation Park. The statue of General Lee and Traveller was later removed and melted down. The park is now given the uncontroversial label of Market Street Park. (East Market Street and 1st Street, near the Downtown Mall in Charlottesville.)

(Copied with grateful appreciation from https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/clam-chowder-howard-johnson-jacques-pepin-way/)

Jacques Pepin

“Fried clams and New England clam chowder were popular menu items at Howard Johnson’s, and I soon learned to love them,” wrote Pepin, who now lives in Madison, Conn.

He then made the chowder was in 3,000-gallon amounts, but he reproduced the taste with this recipe – “when a bit of Howard Johnson’s nostalgia creeps in.”

5 quahog clams or 10 to 12 large cherrystone clams

4 cups water

4 ounces pancetta or lean, cured pork, cut into 1-inch pieces (about ¾ cup)

1 tablespoon good olive oil

1 large onion (about 8 ounces), peeled and cut into 1-inch pieces (1-1/2 cups)

2 teaspoons chopped garlic

1 tablespoon all-purpose flour

2 sprigs fresh thyme

2-1/4 cups Yukon Gold potatoes, peeled and cut into ½-inch dice (one pound)

1 cup light cream

1 cup milk

¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

Wash the clams well under cold water, and put them in a saucepan with 2 cups of the water. Bring to a boil (this will take about 5 minutes), and boil gently for 10 minutes. Then drain off and reserve the cooking liquid, remove the clams from their shells, and cut the clams into 1/2 –inch pieces (1-1/2 cups). Put the clam pieces in a bowl, then carefully pour the cooking liquid into another bowl, leaving behind any sediment or dirt. (You should have about 2-1/2 cups of stock.) Set aside the stock and the clams.

Put the pancetta or pork pieces in a large saucepan, and cover with the remaining 2 cups water. Bring to a boil, and boild for 30 seconds. Drain the pancetta, and wash it in a sieve under cold water. Rinse the saucepan, and return the pancetta to the pan with the oil. Place over medium heat, and cook gently, stirring occasionally, for 7 to 8 minutes. Add the onion and garlic, and continue cooking, stirring, for 1 minute. Then add the flour, mix it in well, and cook for 10 seconds. Add the reserved stock and the thyme, and bring to a boil. Then add the potatoes and clams, bring to a boil, cover, reduce the heat to very low, and cook gently for 2 hours.

At serving time, add the cream, milk, and pepper, bring to a boil, and serve. (Note: No salt should be needed because of the clam juice and pancetta, but taste and season to your liking.)

© 2015 New England Historical Society

Many people were fond of the late, great, outsider-artist-philosopher Jonathan Bowden. And why shouldn’t they be? Surely he was at least as sound as our good friend Thomas Francis.

Edward Dutton

Shaman of the Radical Right:

The Life and Mind of Jonathan Bowden

With a Foreword by Greg Johnson

Perth, W.A., Australia: Imperium Press, 2025When Edward Dutton published this investigatory biography of Jonathan Bowden a few weeks ago, he promoted it with an amusing little fillip on his Substack. At the start of a loose, impromptu podcast about his new book, Dutton gives us a vocal impersonation of Bowden himself—speaking to us from beyond the grave, as it were. This “Bowden” has just learned that someone’s published a book about him, and it all sounds like an excellent idea. He hectors us to go buy this new book, because it’s all about him.

Vocally the Dutton impersonation is not exactly like Bowden, to my ears anyway (register too high, voice too strangled-sounding), but it is funny, and does catch the cadence and improvisational panache of Bowden’s speeches. For example, there’s a wonderfully misplaced quote when he’s plugging the book, very Bowdenesque: “I think it was Benjamin Disraeli, Benjamin Disraeli— he was one o’ them—Benjamin Disraeli, he said, ‘If a book is worth reading it’s worth buying!’”

READ THE WHOLE GODDAMNED THING! HERE!

https://counter-currents.com/2025/03/artist-philosopher-shaman-liar/

(Originally published in Counter-Currents,

October 23, 2018.)

Surely, Ian Fleming’s final book, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, is also his finest work of fiction. Published 54 years ago this month, shortly after Fleming’s death, it is visibly superior to the James Bond books in so many ways.

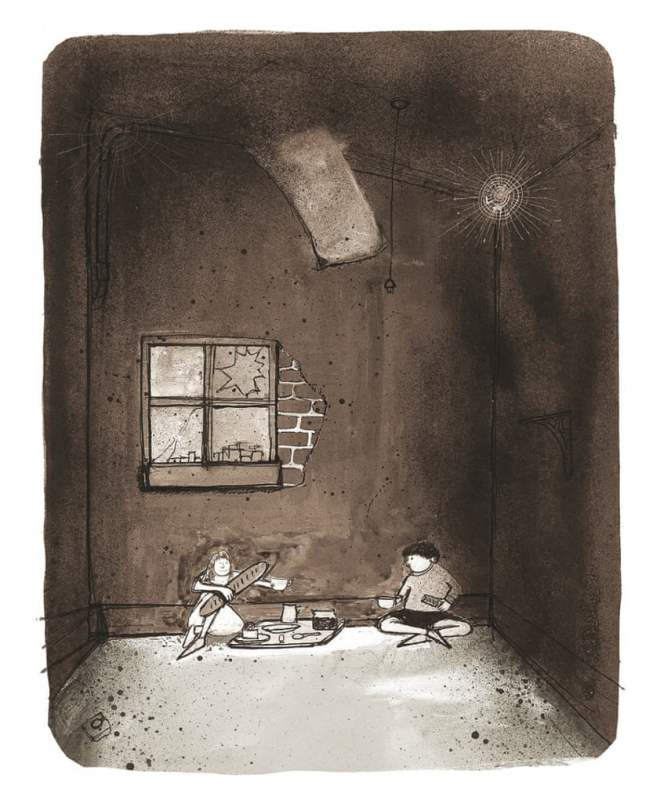

For one thing, it has pictures. Fleming and his editors struggled long and hard to select the right illustrator. The drawings by the illustrator who was eventually selected, John Burningham, are note-perfect and meld perfectly with the text. They’re drawn in the sloppy-intuitive school popular among British illustrators of the era (see also Paul Hogarth, Ronald Searle, and Ralph Steadman), and are almost entirely in black-and-white, or rather black-and-greys.

They complement the text without dominating it, the way precise, overdrawn, four-color paintings in kiddie books always seem to be these days. The Burningham stylization makes the pictures somewhat reminiscent of Edward Gorey, although shading is mostly done by loose ink-wash rather than india-ink cross-hatching. As an example, see the below illustration, of two children with a baguette in a decrepit room.

I must emphasize, of course, that I am discussing only the Ian Fleming book here, and not the 1968 movie musical of the same name starring Dick Van Dyke. That film is a curious creation, too, but it has an almost completely different story, written by Roald Dahl. The film has a big, sentient motorcar that flies, but that’s pretty much it. The movie Chitty is set in a different era and landscape – part Edwardian England (à la Mary Poppins), part Brothers Grimm.

Dahl’s imagination had some parallels with Fleming’s, but was much crueler and more transgressive. For example, Fleming would never have come up with a horrifying figure like Dahl’s Child Catcher, who steals away Jeremy and Jemima and locks them in a mobile cage. In the Fleming version, the children are indeed kidnapped, but by stock movie villains out of a 1950s French gangster film, or maybe an Ealing comedy. And the gangsters give the children jam and baguettes for breakfast because (explains the author) that’s what you eat for breakfast when you are in Paris. Even though he’s writing about a flying car, Fleming keeps his tale recognizably rooted in Mother Earth.

Speaking of variant versions, if you want to read the real Chitty, be sure to hunt down an edition with those original John Burningham drawings, because it may not be available at your kiddie-book counter. Alternatively, take a glance at the “potted” version of the book featuring Burningham illustrations that Fleming’s nephew provided to the Guardian for Chitty’s fiftieth anniversary in 2014. Originally, Fleming wanted the political cartoonist Trog (Wally Fawkes), but Trog’s newspaper editor nixed the plan because Fleming’s work was usually serialized in a rival newspaper. This was an unexpected bit of luck. Nobody drew better than Trog, but Burningham’s ink-wash dreamscape was a far better choice for Chitty.

By all means shun any Chitty edition with some later dauber’s efforts – those overly colorful and hyper-detailed ones. And avoid like the plague those brummagem titles (Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and the Race Against Time, e.g.) that were cranked out by later authors, in much the same way that every writer from Kingsley Amis on down had to take a crack at writing a James Bond thriller after Ian Fleming died. Chitty is not a franchise. As the imitation Bond books demonstrate all too well, the Fleming wit is not susceptible to replication.

I keep dwelling on those original Burningham illustrations because they not only match the Fleming text, but they capture the grey 1950s sensibility that you get in the British cinema of the era. Off the top of my head, I think of the film version of John Osborne’s The Entertainer (directed by Tony Richardson), and Basil Dearden’s excellent The League of Gentlemen. Both films were released in 1960, but are set a few years earlier, so are pretty much contemporary with Fleming’s Chitty. They depict a squashed-down, etiolated England (or “Britain”), still listless and crippled from the War and Austerity. Vestiges of Imperial and martial glory still abound, but they are dusty and repellent, like Miss Havisham’s wedding cake.

The atmosphere is all very much Angry Young Men stuff, like Lindsay Anderson’s famous 1957 essay where he says, “Let’s face it; coming back to Britain is always something of an ordeal . . . And you don’t have to be a snob to feel it. It isn’t just the food, the sauce bottles on the café tables, and the chips with everything.”

In the Dearden movie, Jack Hawkins – that matchless cinematic colonel – gathers together a clutch of former officers and gentlemen (Bryan Forbes, Richard Attenborough, Richard Livesey, et al.) who did very well in the War, but not at all well since. One is a cuckold in an old-school tie who runs illicit gambling parties; one is a homosexual ex-Blackshirt who now works as a physical trainer; another is a fake clergyman with a string of sex scandals. The Jack Hawkins colonel treats them to a lunch in an upstairs suite at the Café Royal (it looks more like a catering room in Torquay), and reveals his master plan for a great bank robbery. Later, they are rehearsing the robbery plot in a script-reading room when a theatrical queen (a young, camp Oliver Reed) flounces in, looking for Babes in the Wood rehearsals. “No, we’re rehearsing Journey’s End,” Hawkins replies. Journey’s End, indeed; their country has let them down, and now Hawkins & Co. are going to get their own back, through esprit and ingenuity.

And this is the background theme to Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Commander Caractacus Pott (Royal Navy, like intelligence officer Ian Fleming) is a brilliant man and inventor, but has not done well for himself and his family. His inventions don’t catch on. The Potts are poor; they don’t even have a car. Then Commander Pott accidentally creates a candy that makes him a tiny fortune. They shop for a car. But the eccentric Potts doesn’t want to be like the other people they see, clogging up the motorway in their little black beetles. They must have a vehicle that is somehow special.

In a junkyard, an early 1920s racing car seems to call out to them, with the portentous license plate GEN II. This, of course, is Chitty Chitty Bang Bang herself (based on a bizarre, but very real racing car, Chitty Bang Bang, that young Ian Fleming recalled from the early 1920s). The old car was about to be sold for scrap. But Commander Pott buys her and, with a little bit of tinkering, gets her on the road. The family decides to go to the beach on a fine day, but they find the road clogged with thousands of the despicable black beetles. So Chitty spreads out her wings and soars above the lesser folk, landing on a lone beach available only at low tide. Then, Chitty and the Pott family “swim” the English Channel and end up in France, where adventures and gangsters await.

Ian Fleming wrote Chitty Chitty Bang Bang in the spring of 1961, and did it very quickly, because it was just a series of stories about a “magical car” that he had made up as bedtime tales for his son. Its publication in late 1964 coincided with the release of the Disney movie Mary Poppins. What curious antipodes of juvenile entertainment! Fleming’s subtle and inadvertent Angry Young Man critique of 1950s British society, coming up against a fanciful picture of a pre-1914 England, when everyone had a nanny, and the most visible revolutionary movement was Glynis Johns and her suffragettes.

But there was one beneficiary to this cultural collision. Fleming’s successor as kiddie-bestseller author was his friend Roald Dahl, whose entrée into children’s books, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, came out at almost the same time as Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Accordingly, Dahl was the obvious, immediate choice to write the Chitty movie script. And so Dahl wrote his mad and perverse – albeit commercially successful – film of Chitty. It had little to do with the original book, but it carved out for him a whole new career as a children’s author (James and the Giant Peach, Matilda, The Fantastic Mr. Fox, etc., etc.).

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory has been filmed twice. Surely it’s time for Chitty Chitty Bang Bang to get the film it deserves. Black-and-white. No songs. In the 1960 directorial style of Basil Dearden.

One of the worst things I ever did happened in 1992. I was leaving the bar called The Bar (RIP) on Second Avenue and 4th Street to go to a party called Tattooed Love Child at another bar, Fez, located in the basement of Time Cafe (RIP x 2). TLC was held on Wednesdays (Thursdays?), and I often went to The Bar after work for a few hours so I wouldn’t have to go all the way home first. So it was probably 10-ish, and I know it was late winter/early spring because I was carrying a copy of the completed manuscript of my first novel Martin and John, which I’d just turned in to my publisher that very day. Which makes me 24 and old enough to know better. Or who knows, maybe this was exactly the age to learn this kind of lesson.

What happened was: I was halfway down 4th Street when I heard someone yelling. I turned to see a large fellow running after me. At first I wondered if I was getting gay-bashed. But even though this guy didn’t set off my gaydar he still didn’t seem particularly menacing. When he got closer I clocked the pleated khakis (this was the era of the ACT UP clone—Doc Martens, Levi’s tight or baggy, and activist T-shirts—which look I had embraced fully) and rust-colored Brillo hair. I love me a good ginger, but you gotta know how to style it, especially if it runs frizzy. And so anyway, this guy, whose name was Garfield but said I could call him Gar, told me he’d been in The Bar but had been too shy to talk to me and decided to try his luck on the street. As politely as I could, I told him I wasn’t interested. He asked me how I could know I wasn’t interested when I didn’t know him, which was an invitation for me to tell him that not only did he look like a potato, he dressed, talked, and ran like a potato. Alas, I chose not to indulge his masochistic invitation.

He asked where I was going and I told him. He asked if he could go with me and I told him he could go to Fez if he wanted but he shouldn’t think he was going with me. He came. I quickly learned that he’d mastered the art of speaking in questions, which put me in the awkward position of answering him or ignoring him, which made me feel rude even though I’d told him I wasn’t interested. When he found out I was a writer he got excited and said I must love the New Yorker! I told him I hated the New Yorker. He asked how I could hate the New Yorker and I told him that besides the fact that the New Yorker published shitty fiction (plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose), and the only gay fiction it published was assimilationist and boring, there was also the fact that an editor there (Dan Menaker, if we’re naming names) had rejected a story of mine by suggesting in his correspondence with my agent (by which I mean that he wasn’t embarrassed to write this down, let alone worried about repercussions) that psychological problems were preventing me from creating effective fiction. (By the way, fuck you, Dan.) None of which made any sense to Gar. The New Yorker was important so I must love it. I just didn’t know I loved it yet. Or something like that. At some point in this exchange I remember saying something along the lines of Look, I’m just going to apologize now, because it’s pretty clear that sooner or later I’m going to say something really offensive to you and your feelings are going to be hurt. I don’t want to do that, but you’re clearly not getting the fact that you and I don’t look at the world the same way, and you keep thinking that if you hang around long enough we’re going to find common ground, when all you’re really doing is making our differences that much clearer. He laughed at this, one of those confused/nervous/defensive laughs, and if I’d been more mature I would have been more blunt and told him to get lost. But I too was a little deluded. I thought he had to get the hint eventually. But although I understood pretty much everything else about him, I failed to reckon fully with his lack of self-respect.

I told him I hated the New Yorker.

So: we got to Fez, where I ran into my friend Patrick (Cox, I think, but it’s been a minute), who looked at me like, What are you doing with this weirdo? I wouldn’t let Gar buy me a drink and I did my best to exclude him from my conversation with Patrick but he still wouldn’t take a hint. He must have hung around for a good hour. My answers to his questions grew more and more peremptory. Bear in mind I wasn’t disagreeing with him or dismissing his opinions just to get rid of him: we really had absolutely nothing in common. But we both read the New Yorker and we were both gay and we both wore clothes to cover our nakedness so clearly we were birds of a feather. Finally he said he had to leave. He asked for my number. I remember Patrick laughing in his face, but maybe that’s just because I wanted to laugh in his face. I was like, Are you serious? And he was like, We have so much in common, we should get to know each other better! When I was fifteen years old a pedophile used that line on me in the Chicago bus station, and if I’m being honest I had more in common with the pedo, who was about 50, black, and urban, while I was a white teenager from rural Kansas, than I did with dear old Gar. I told him I wasn’t going to give him my phone number or accept his. He seemed genuinely shocked and hurt, which of course made me feel like shit, which of course made me mad, because why should I feel like shit when I’d spent all night trying to rebuff him? He asked what he would have to do to get me to go out with him. Without thinking, I said, Take a good look at yourself and your world, reject everything in it, and then get back to me. It was the kind of soul-killing line people are always delivering in movies but never comes off in real life, mostly because even the most oblivious, self-hating person usually has enough wherewithal to cut someone off before they’re fully read for filth. I believe I have indicated that Gar did not possess this level of self-awareness. His face went shapeless and blank as though the bones of his skull had melted. For one second I thought I saw a hint of anger, which might’ve been the first thing he’d done all night that I could identify with. Then he scurried away.

Now, I’ve said shitty things to people before and since, but this one’s always stuck with me, partly because, though I’m a peevish fellow, it’s rare that I speak with genuine cruelty, and when I do it’s because I’ve chosen to. This just came out of me. But mostly I remember it because I knew I’d seriously wounded this guy, which, however annoying and clueless he was, was never my intention. I was and still am a very ’90s kind of gay, which is to say that I believe in the brotherhood of homos and the strength of our community, that however different we are we’re all bound together by the nature of our desire and the experience of living in a homophobic world. When one of your brothers fucks up, you school him. Sure, you might get a little Larry Kramer about it, but you don’t go all Arya-and-the-Night-King on his ass.