“It is an actual historical fact,” says retired professor and history writer Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr., “that the greatest mass murder of African Americans in United States’ [sic] history took place during the New York Draft Riots of July 1863, which were the greatest riots in American history.”

That’s what he said, this historian: “an actual historical fact.” Not only the greatest mass-murder of African Americans, but it all got to happen during the greatest riots in American history! Now, Prof. Mitcham is merely promoting his little book, The Greatest Lynching in American History: New York 1863 (Shotwell Publishing, 2020), so perhaps we should permit him some hyperbole. Still, I doubt anyone who remembers Watts or Detroit or Newark in the 1960s—or the nationwide BLM/Antifa riots of 2020—could agree with that last part. Greatest riots, truly?

As to “mass murder,” documented sources can name only about 10 negroes (as we all used to say until about 1972) who were beaten to death or lynched in New York City between 13 and 18 July 1863. Mitcham declares there must have been 200 blacks killed, on no basis other than his own fevered imagination. And even 200 isn’t that big a number in comparison with the hundreds of phantom deaths that black activists Ida M. Bell and W. E. B. DuBois used to conjure up a century or more ago, when ringing up the totals from race riots: they counted any missing negroes as lynching victims.

Mitcham’s little book is thus another entry in the genre of Lynching Porn, along with such dubious, inventive pulp-histories as Herbert Asbury’s The Gangs of New York (Knopf, 1928) and Barnet Schecter’s The Devil’s Own Work (Walker Books, 2005), both of which Mitcham leans heavily upon for source material. Mitcham is also totally wild on the subject of how many people were killed in the riots. Careful scholarship and documentation have long since pinned that number down to a hard 119, including soldiers, police, and accidental deaths. Mitcham wants to believe it’s somewhere between 1,200 and 1,500. Those were estimates floated by the NY Metropolitan Police and the War Department in the immediate post-riot hysteria, before anyone took the time to check the records.

What’s weird about Mitcham is that, to judge by his other writings, he’s not some anti-Copperhead crackpot who wants to hang Jeff Davis from a sour apple tree. He’s something of a Southern patriot, in fact, as are many authors in the Shotwell Publishing imprint. I just don’t get it. Perhaps Mitcham imagined that deriding pro-Confederate New York City could be a good way of sticking it to the Yanks.

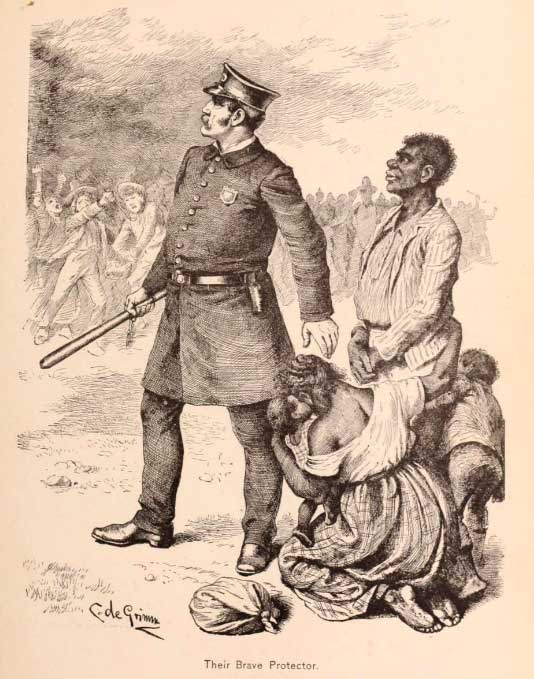

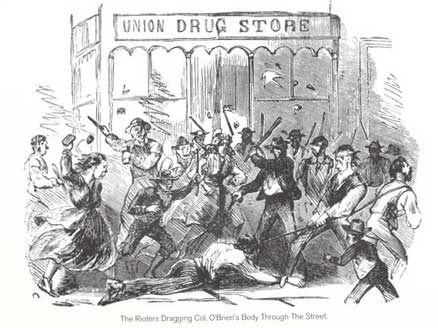

James Gordon Bennett Jr. of the NY Herald used this cartoon, depicting July 1863, for a piece honoring the New York Metropolitan Police in 1884. Constantin de Grimm was a famous European satirical illustrator.

“The Sky Was Black!”

A few years back I wrote about the burning and sacking of the Colored Orphan Asylum at Fifth Avenue and West 43rd Street. This conflagration often figures as a gleaming centerpiece of the July 1863 “Draft Riots” narrative, in spite of the fact that no one died in that arson, nor was anyone ever prosecuted for it. Since much of the surrounding neighborhood was also put to the torch—including a hotel, a stockyard, and an ice cream parlor—local cognoscenti maintained it was all part of an urban-renewal plan. The City wanted to get rid of eyesores and low-rent tenants on City-owned plots between 42nd Street and the lush new Central Park at 59th, soon to be the most expensive real estate in the world. About the only building in that region that still stands today is St. Patrick’s Cathedral—then unfinished—along with its Tuckahoe-marble rectory and parish house: all built on private land donated to the Archdiocese.

But even more renowned than the burning of the black orphanage (which was actually a fee-paying, partly charitable boarding school) are the endless fables about innocent negroes being suddenly plucked off the streets and strung up on a tree or lamppost. “The sky was black with hanging negroes!” runs an ignorant cliché. However I have found only about a half-dozen of these documented in news reports of the time, and they mostly follow a similar pattern: negroes shoot white people, they get captured, beaten, and often hanged.

As reported in the New York World of July 14, 1863:

An intense excitement was created in the vicinity of Bleecker Street and Sixth Avenue last evening [July 13], in consequence of a white citizen being shot while passing up Bleecker Street… A gentleman…was going to his home, when he was accosted by a partially intoxicated negro, who was so abusive in his language as to provoke a quarrel. Some altercation ensued from this abuse, when the negro drew a pistol and shot the white man, who soon after died. [A crowd gathered, chased the negro to the old St. John’s Cemetery on Carmine Street, beat him, hanged him, cut his throat, and built a fire beneath him.]

And in the Daily News—same day, same neighborhood:

About eight o’clock last evening four negroes were seen running down Carmine Street, with a large crowd in close pursuit. One of the negroes being overtaken, turned and fired upon his pursuer, shooting him with three bullets, and killing him instantly. The negroes then separated, each taking a different route. [The crowd] pursued the first to near the corner of Varick Street, where he was secured and very badly beaten…then hung from a tree. The field was then left to a party of boys, who amused themselves by building a fire…

Which Paper Do Ya Read?

It made a big difference which paper you read. Henry Raymond’s stridently Republican New York Times appears to have combined elements from both the above stories and added extra details, while leaving out the crucial fact that it all began when a negro shot and killed a white man. The imaginative spin is breathtaking:

There were probably not less than a dozen negroes beaten to death in different parts of the City during the day. Among the most diabolical of these outrages that have come to our knowledge is that of a negro cartman living in Carmine Street. About 8 o’clock in the evening as he was coming out of the stable, after having put up his horses, he was attacked by a crowd of about 400 men and boys, who beat him with clubs and paving-stones till he was lifeless, and then hung him to a tree opposite the burying ground. Not being yet satisfied with their devilish work, they set fire to his clothes and danced and yelled and swore their horrid oaths around his burning corpse. [July 14, 1863.]

The Times is really winging it here. “Not less than a dozen negroes beaten to death”—we don’t know where or how, but that’s our story and we’re sticking to it. Similarly, when writing up the Colored Orphan Asylum’s destruction, which happened around the same evening, the Times claimed that the school housed “600 to 800” colored children, although the true number was 230.

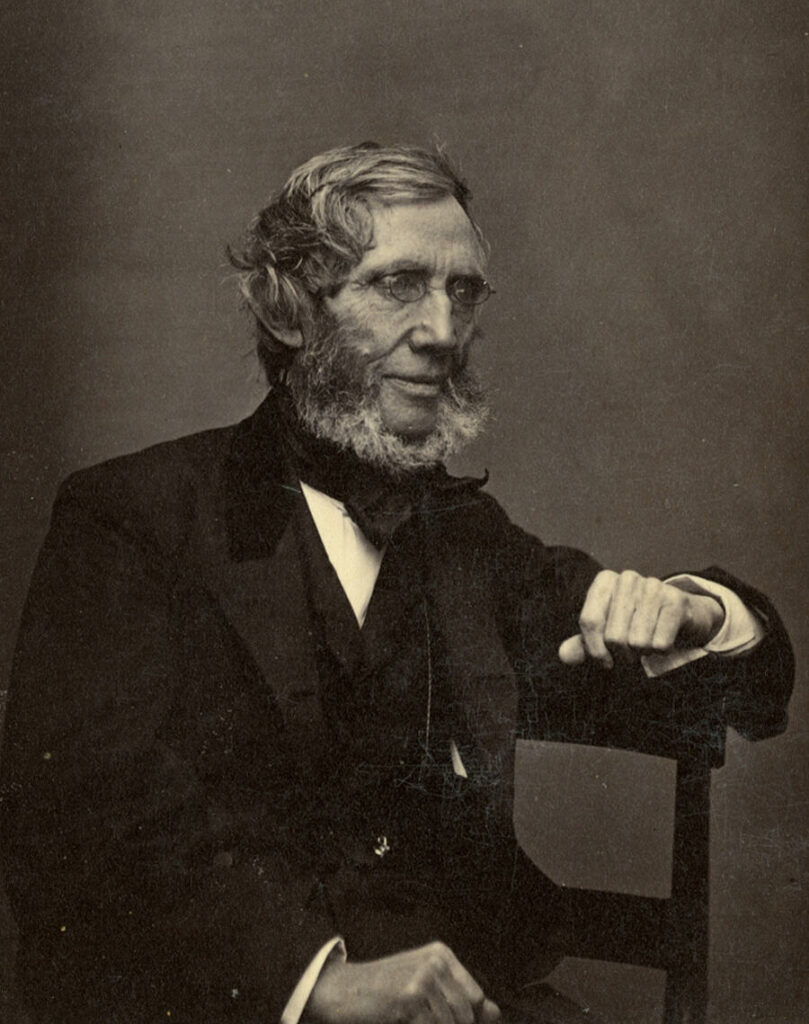

Then you have personal reports in letters and diaries, equally imaginative and based almost entirely on hearsay. An elderly Columbia chemistry and botany professor, John Torrey (1796-1873), saw no mob violence in the street, but he heard tales and readily believed what people told him. As Torrey wrote in a letter on July 15th:

This morning I was obliged to ride down to the office in a hired coach. A friend who rode with me had seen a poor negro hung an hour or two before. The man had, in a frenzy, shot an Irish fireman, and they immediately strung up the unhappy African. At our office there had been no disturbance in the night. Indeed the people there were “spoiling for a fight.” They had a battery of about 25 rifle barrels, carrying 3 balls each, & mounted on a gun-carriage. It could be loaded & fired with rapidity. We had also 10-inch shells, to be lighted & thrown out of the windows. Likewise quantities of SO3, with arrangements for projecting it on the mob. Walking home we found that a large number of soldiers—infantry, artillery & cavalry are moving about, & bodies of armed citizens. The worst mobs are on the 1st & 2nd & 7th Avenues. Many have been killed there. They are very hostile to the negroes, & scarcely one of them is to be seen. A person who called at our house this afternoon saw three of them hanging together.

Professor Torrey in the 1860s.

Quite a bit to unpack here. A frenzied negro is said to have shot an “Irish fireman,” and was immediately strung up. Is the story true? And if so, how and why did he draw a bead on the “Irish fireman”? And how did Torrey’s friend know the victim was Irish? Because most firemen were? Or because that fit in with a current narrative? No matter: Torrey and friend agree the negro gunman shouldn’t have been hanged, but rather should have got off scot-free, just on general principle. Torrey seriously thinks negroes are being hanged all across the city, and readily believes a visitor who claims to have seen “three of them hanging together.”

The side note about Torrey’s office crew at the downtown Columbia campus is also amusing. They’re preparing to defend themselves with rifles at the windows, globular bombshells, and sulfur trioxide, which I take to be an early and very painful version of tear gas. Another science-professor whiz at Columbia, Richard Sears McCulloh, also liked to build gas bombs, and soon would leave New York City for Richmond, to develop such dainties for the Confederacy. So it appears this was an ongoing research interest at Columbia College.

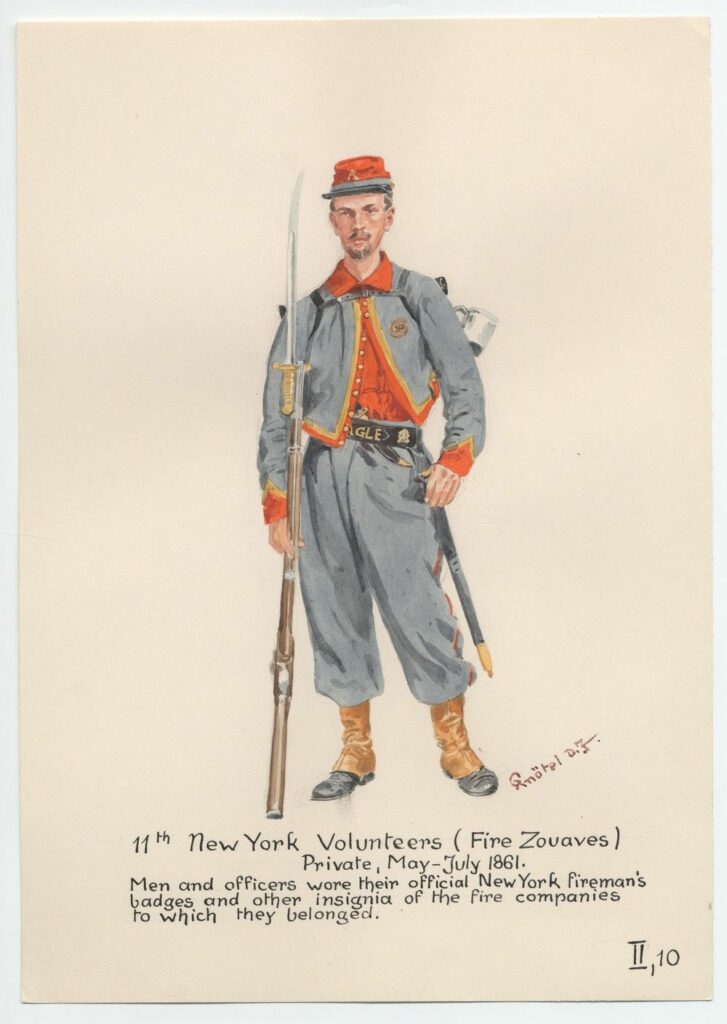

As for that encounter between the negro and the “fireman,” the newspapers give us a “synoptic” version of the story. It appears the excitement got started when the negro shot and killed a veteran of the “Fire Zouaves” (a now-disbanded Union regiment of firemen also called the 11th New York Volunteers).

From the Daily News of July 16th:

At half after six yesterday morning a middle-aged negro, named Potter or Porter, was passing quietly down Thirty-second street, near the [Seventh?] avenue, when he was met by a fireman, an ex-Zouave, named Manney, who hailed him, asking where he was going. The negro not understanding, apparently, what was said, made no reply, and Manney, with the most kind intentions, told him that the excitement was very great, that the mobs would certainly be around today, and would doubtless kill him or severely beat him, if they should catch him. Still, apparently misapprehending Manney’s intentions, and probably misunderstanding his language, the negro drew a revolver and discharged it with fatal effect. He shot twice, certainly, each ball striking Manney full in the forehead, and entering his brain. He then started to run, but was soon overtaken by a crowd of excited and infuriated people, and by several of the firemen residing near by, who chased him a short distance, and soon overtook him. The heart sickens at the recollection of the fearful and

DREADFUL SCENE

which followed. The negro was pounded, battered, kicked, pummelled, stoned, thrown down, trampled upon, and fairly bruised into a jelly. A bloody pulp was all that was left of the mistaken murderer in a very few moments; but even this was considered slight revenge, and the mutilated mass of blood and bones and quivering flesh was carried brutally to a tree, to a limb of which it was hung, amid the cheers and jeers of the indignant crowd.

Poor Manney had the best of medical attendance, but probably for naught…

No good deed goes unpunished! West 32nd Street seems to have been a hotbed for this kind of shooting/lynching. On the evening of the same day (July 15) there was a crowd of “between four and five thousand men” gathered near the corner of Eighth Avenue, per the New York Herald. They were awaiting the arrival of Federal troops fresh from Gettysburg, and they weren’t sure whether to welcome them or take to the barricades.

But first there was a distraction. From the July 16 New York Herald:

A negro unfortunately made his appearance, when one of the men called him an opprobrious name. The negro made a similar rejoinder, and after a few words the indiscreet colored man pulled out a pistol and shot a man. With one simultaneous yell the crowd rushed on him. He was lifted high in the air by fifty stalworth [sic] arms and then dashed forcibly on the pavement. Kicks were administered by all who could get near enough. Some men then took hold of his legs and battered his head several times on the pavement. Life was now nearly extinct and a rope was called for. The desired article was in a moment produced and the black man’s body was soon after suspended from a neighboring lamppost.

There are also instances of white people being shot by negroes who manage to run away. But these accounts are much shorter, as there’s no payoff in the end, and little newsworthiness.

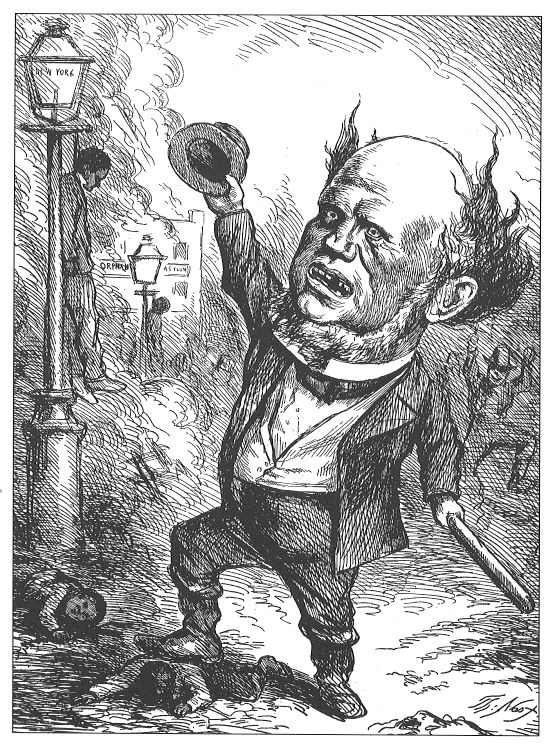

The ever-tasteful Thomas Nast caricatures Governor Horatio Seymour, blames him for the negro lynchings and the burning of the Colored Orphan Asylum (in background).

Is There a Backstory?

Needless to say, these narratives are repetitive and maybe tiresome, apart from their stilted and amusing turns of phrase. And they leave a lot of open questions. For example, how is it that all these angry negroes happened to be “packing”? Well, one obvious answer is that in those days you could buy handguns in your local hardware store. And while I haven’t found precise documentation for this, it seems very likely that New York City negroes had been encouraged to arm themselves, both by white Abolitionists and by firebrand black preachers such as Henry Highland Garnet. The excuse presumably was that the white people in New York would soon be murdering all the blacks they saw, so you’d best prepare. (Often “white” would be euphemized as “Irish,” so as not to offend Caucasian Abolitionists. But as the majority of white people in New York were Irish—whether immigrant or first- second-, or third-generation—this was an frivolous distinction from the negro point of view.) John Brown himself, who definitely wished to arm all blacks for a bloody revolution, had close ties to New York through his local ally James Sloan Gibbons, whom he visited shortly before his Harper’s Ferry raid in 1859.

Gibbons, a financial writer by profession, was perhaps the leading Abolitionist intelligence operative in New York. Supposedly his home had been one of the major safe houses in the Underground Railroad. He was certainly an effective propagandist. He wrote the lyrics to one of the most thumpingly gleeful songs to come out of that war, “We Are Coming, Father Abra’am, 300,000 More,” an 1862 ditty that inspired a half-dozen musical compositions, including one from Stephen Foster, though Foster’s was not the best. Friends of Horace Greeley, the Gibbons family owned a marvelous five-floor townhouse on West 29th Street, then also known as Lamartine Place (a romantic 1840s dedication to the French poet and statesman). The neighborhood still exists today, as fashionable as it was in 1850.

The memory of James Gibbons is enshrined in a memoir written by his daughter, Lucy Gibbons Morse, “Personal Recollections of Draft Riots of 1863.” A not-for-profit calling itself the Riot Relief Fund gives out a little book, The Riot of the Century, to donors and well-wishers, and it contains this peculiar little essay. The writing is full of interesting biases and evasions, but it gives a flavor of Abolitionists’ self-righteousness and sentimentality. The bullying friends of terrorist John Brown are now feeling the terror of the persecuted. As “Riot Week” progresses, little Lucy and her sister hear their house is going to be attacked—they’re just a few blocks from those mobs on 32nd St.—and so they’re preparing to move out of the city. But too late! Their father is off attending strategy powwows at the Fifth Avenue Hotel on 23rd St., so he isn’t there when a mob ransacks the house and drags off their books and pots and piano. The girls watch disconsolately from a top-floor window.

Finally they’re rescued by a family friend, young celebrity lawyer (and future Ambassador to Great Britain) Joseph Choate, who takes them to his house. Lucy and her sister marvel at the “quiet restful order” of the Choate domicile:

It was beautiful—we did not know how beautiful until they told us they had five colored refugees in the kitchen!

Besides this sort of smarm, the essay is distinguished by the deceitful pose of the narrator. She is depicted as a dizzy, befuddled young girl of about nine or ten, or so I thought. It comes as a shock to discover that little Lucy Gibbons was actually born in 1839 and at the time of this tale she an adult, a 24-year-old music teacher.

In the immediate aftermath of the Riots, most press treatments dwelt were shot through with the lurid and sensational. Newspapermen seldom did on-the-spot reporting, preferring to write up incidents they didn’t witness but learned about via telegraph from the police stations and other newspapers. The telegraph was the internet of its day, with all the cop shops and pressrooms wired in to each other. And so the reading public were encouraged to believe that hundreds if not thousands of innocent negroes were being immolated and hung from lampposts, while drunken rioters looted every dry-goods shop they could find. Actually the only notable clothing store to get wrecked was Brooks Brothers on Catherine Street, and that was for a reason that went beyond theft and vandalism. Brooks Brothers was a notorious war profiteer. In 1861 it supplied the New York Volunteers with uniforms made of shoddy—fabric scraps rolled and glued together in a semblance of cloth. Running back from their Bull Run defeat in the rain, these Federals found their clothes disintegrating around them. (Zouaves kept their uniforms on, I believe; they’d used a different vendor.)

A Pause in Sensationalism

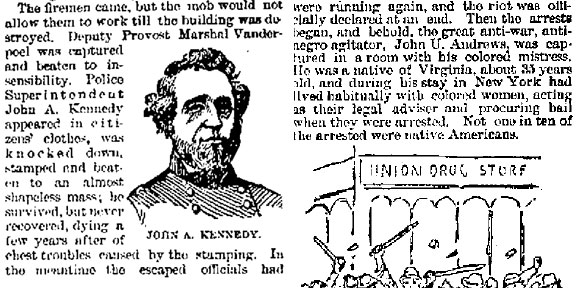

The atrocity tales were eventually forgotten by the public, and even newspaper commemorations of Riot Week turned sedate. Every July, for about 25 years after the war, the Associated Press ran a potted recap of the events, penned by Western historian J. H. Beadle. No gratuitous lynching of black men in the Beadle telling; now the victims of violence were mainly brave police and heroic militiamen. All across the country, in the Cedar Rapids Gazette or the Baldwinsville Gazette and Farmers Journal, readers could thrill year after year to the story of how Police Superintendent John Kennedy was beaten within an inch of his life by a mob outside the draft office on East 46th St.; how doughty Colonel O’Brien was dragged and stamped to death in his own yard at 32nd St. and Second Avenue; and how the great anti-war, anti-negro agitator, Mr. Andrews of Virginia, was captured in a brothel with his colored mistress.

Sensationalism returned in the 1920s with the pulp-fiction histories of Herbert Asbury. Asbury discovered that one could cobble together spicy “true crime” stories by pillaging old newspapers at the New York Public Library. He researched an article that began as an architectural history of lower Manhattan but quickly turned into a fantasia about low dives and large harlots. After this piece was published in The American Mercury, as “Days of Wickedness,” Asbury expanded it with dubious legends of 1830s street ruffians. He called the new manuscript The Gangs of New York. To give the book extra piquancy he put in a long lurid section about the “rioters” of July 1863, and added every atrocity he could research or invent. In Asbury’s telling, most of the rioters lived in Five Points in Lower Manhattan, rather than Chelsea, Kips Bay and Midtown, as the records show. (Five Points’s heyday was actually around 1812.) And many rioters apparently were madwomen who liked to mutilate dying negroes, slice open their “quivering flesh,” fill the wounds with oil, and set them aflame. Contrary to The Gangs of New York, most people in the so-called “Draft Riots” weren’t gang members at all, just as few were protesting conscription. (Most were ineligible for the draft anyway, due to age, sex or nationality.) But this didn’t seem to matter, since Asbury was making up much of his narrative. He secured a very fine publisher, Alfred Knopf, but the book was taken to be light entertainment. No one confused it with serious history.

That was 1928. A few years later the Riots figured in a piece of fiction by Robert W. Chambers, clearly influenced by Asbury’s imaginings. The story was written as a movie treatment for a Civil War film starring that celebrated comedienne, Marion Davies (Operator 13, 1934). Alas, the New York scenes were cut.

So far as I can tell, the “Draft Riots” reentered mainstream consciousness in the 1960s as a sort of rationalization for the many race riots and civil-rights protests during that turbulent decade. It was a way of saying, “It’s okay if Negroes need to let off a little steam; in the 1800s white people (or ‘the Irish’) did it too.” That was in fact the basic pitch of James McCague’s The Second Rebellion (1967), one of the first serious attempts in modern times to treat the July 1863 events as history. Unfortunately McCague drew too much upon the Asbury version. And like Asbury, he was defeated by a mare’s nest of scattered, inconsistent, and highly politicized newspaper stories.

Some Cases of Mistaken Identity

Both Asbury and McCague introduce us to a supporting player who is almost—but not quite—totally fantastical. That is Colonel H. J. O’Brien, or perhaps Col. Henry J. O’Brien. He is a foolhardy, or maybe intoxicated, man on horseback who leads 150 raw recruits down Second Avenue to face a mob at the corner of 34th Street. It is July 14, 1863. The Colonel’s men set up howitzers in the street and, like Napoleon in 1795, offer the crowd a whiff of grapeshot. Many are wounded, some die. O’Brien fires his pistol and orders the crowd to disperse. Unfortunately he shoots and kills a woman holding a baby. Some hours later, O’Brien returns to this neighborhood with a cart—he lives a couple of blocks down the avenue—to see if the mob have looted his house. They have. He goes to his friend Mr. von Briesen’s pharmacy on the corner of 34th St. for a drink of water, or maybe something more fortifying. The crowd apprehends him when he exits, and they beat him to a pulp. The Rev. William Clowry of nearby St. Gabriel’s Church strolls by, sees O’Brien is dying, gives him Extreme Unction. O’Brien gets dragged into his own backyard, where the mob beats him again. Finally Father Clowry returns with a wheelbarrow and takes him to Bellevue Hospital, where he is pronounced dead.

That’s as clear an account as you’ll ever find. However, there is no such person as H.J. or Henry J. O’Brien who fits the time and place. There was no Col. Henry O’Brien at all. There was a Lt. Col. James O’Brien, of the 48th Massachusetts, recently killed during a heroic assault at Port Hudson on the Mississippi. Our unfortunate fellow with the horse and cart is most likely Mr. Henry F. O’Brien, 43 years of age, address 559 Second Avenue. Still a British subject, but he recently filed for naturalization. Henry F. was briefly commissioned as lieutenant, then captain, at the end of 1862, but he only lasted two months and saw no action. I hear Fredericksburg was a huge black pill for Union morale. He resigned.

Anyway, a few months later Henry F. comes up with the idea of reconstituting the 11th New York Volunteers—the Fire Zouaves! I don’t know if they were planning to wear those snazzy French-Algerian Zouave outfits. The 11th had a very poor record during their one year of existence, but if Henry F. gets enough recruits for his new regiment he can style himself a colonel!

This is right after the Union defeat Chancellorsville, and the Federals seem willing to take anyone. And thus we get the legend of Col. Henry O’Brien…a figure yet unknown to the Adjutant General and War Department.

O’Brien’s terrible, though probably deserved, death brought Henry F. a measure of international fame. Somebody in Sheffield, England read the gruesome tale and thought he recognized an old neighbor. As reported July 29th in the London Telegraph:

The correspondent of a Sheffield paper expresses his belief that the Colonel O’Brien who was lately hanged to a lamppost in New York, cut down before he was dead, and then brutally murdered by the mob, was the Colonel M. D. T. O’Brien who had been a resident in Sheffield for some time, and who was well known to many of the leading families in that quarter under the name of Thompson, his mother’s maiden name. The colonel had formerly seen some service in the Crimea, and had been in Italy with Garibaldi. In December he sailed for New York and was slightly wounded in the battle of Fredericksburg.

If only the “Colonel” could have lived to see this!

Facebook Comments