The Very Last Word (We Hope) on Emmett Till—D R A F T

Today we bring you more breaking news on the 1955 murder of Emmett Till. And as always, the story is: there is no new news about Emmett Till.

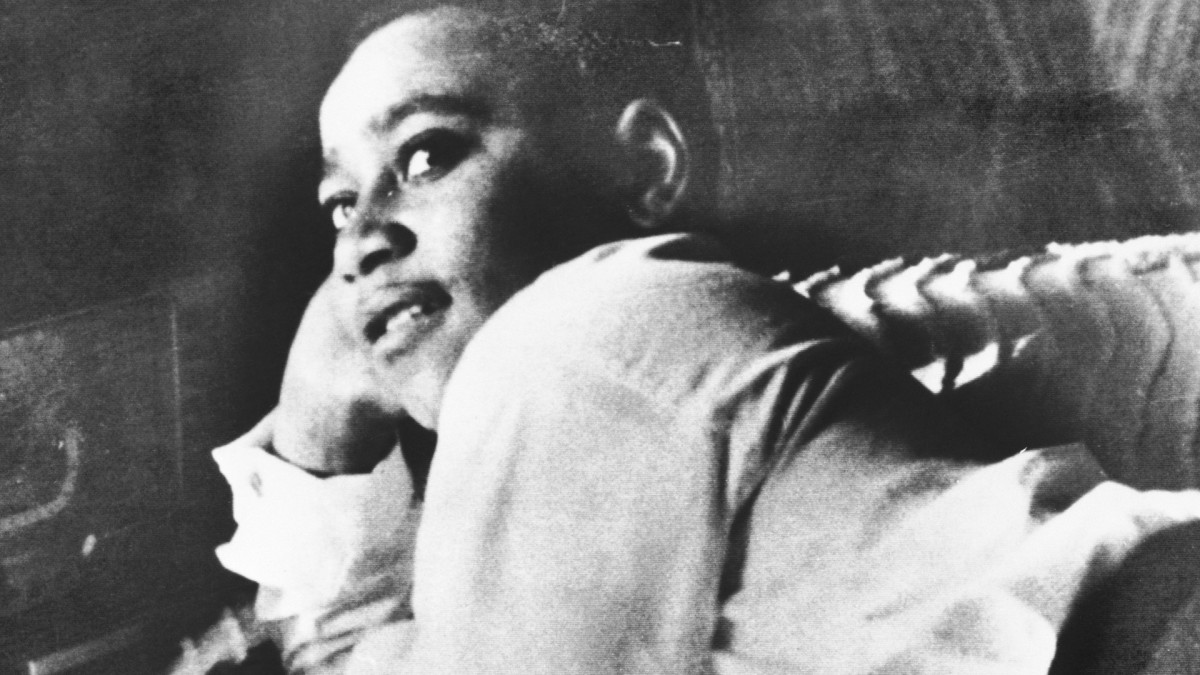

It’s now been 67 years since the the beefy 14-year-old Chicago negro boy (as we used to say) was beaten and slain in Mississippi, a few days after grabbing and crudely propositioning a young white woman in a country store. Year after year we are promised new revelations and fresh insights about the case, but they never materialize. But this doesn’t stop the never-ending Emmett Till news cycle. Just recently (August 9, 2022) the New York Times spent a thousand words advising us there would be no new indictment or reinvestigation of the 1955 killing. (Mississippi Grand Jury Declines to Indict Woman in Emmett Till Murder Case.) Thank you for that update, New York Times!

A few weeks earlier, the Times’s ever-aggrieved African-American Charles Blow wasted a column telling us that 88-year old Carolyn Bryant Donham, the lady Till molested in 1955, is still a bad sort, an unpunished criminal, a key player in the Till murder (Shed No Tears for Carolyn Bryant Donham). Blow’s argument goes something like: if Carolyn hadn’t been standing there at the counter of her little grocery store in Money, Mississippi on August 24, 1955, then Emmett “Bobo” Till wouldn’t have been able to assault and insult her, so then Carolyn’s husband and brother-in-law wouldn’t have beaten and killed him and thrown him in the Tallahatchie River with a cotton-gin fan tied to his neck. In fact, Emmett might even be alive today!

The silliest news angle of recent months must be the one about the 1955 arrest warrant. It seems somebody found the original hand-written warrant to bring Carolyn in for questioning. Black news sites treated this as a major find, a piece of definitive proof that Carolyn was complicit in the murder; a watertight case for arresting and prosecuting the old lady today. Trouble is, Carolyn was already brought into court and questioned, way back in September 1955. Even if the warrant were still valid, it was served and answered a long time ago.

Media and legal harassment of Carolyn Bryant Donham has been going on for many years. Back in 2007, there was another grand jury empaneled in Mississippi, considering an indictment of her for manslaughter in the Till case. She was now 73. Needless to add, there was no new evidence and no indictment.

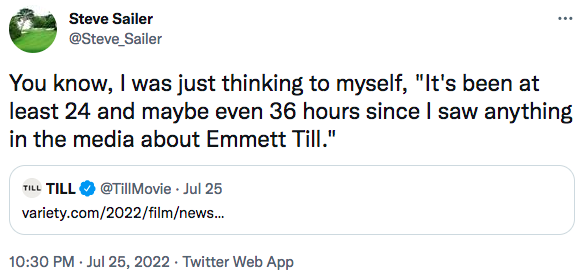

But the Till file newsfeed keeps rolling on, fiercer than ever. Steve Sailer and others on Twitter have a kind of running comedy routine about it. Commenting on a Variety review of a new Emmett Till movie, Steve tweeted, “You know, I was just thinking to myself, ‘It’s been at least 24 and maybe even 36 hours since I saw anything in the media about Emmett Till.’” Whereupon someone responded, “They will still be reporting new details on Emmett Till long after the heat death of the universe.”

The latest gusher of Emmett Till news seems to have begun with a dubious claim by a writer named Timothy Tyson. Way back in 2017, he published a book called The Blood of Emmett Till (Simon & Schuster). Here Tyson says he interviewed Carolyn in 2008, and that she recanted her trial testimony from 1955. Or, as some news stories put, “She admitted she lied.” For a while it was the stuff of screaming headlines and a slick treatment in Vanity Fair.

The latest gusher of Emmett Till news seems to have begun with a dubious claim by a writer named Timothy Tyson. Way back in 2017, he published a book called The Blood of Emmett Till (Simon & Schuster). Here Tyson says he interviewed Carolyn in 2008, and that she recanted her trial testimony from 1955. Or, as some news stories put, “She admitted she lied.” For a while it was the stuff of screaming headlines and a slick treatment in Vanity Fair.

Specifically Carolyn denied the part in her testimony where she said Emmett Till grabbed her by the waist and said “I f—— white women before.” “That part’s not true,” Carolyn told Tyson, as they sat in her kitchen and ate her homemade pound cake.

At least that’s the story Tyson tells. He even opens his book with that scene. They’re in the kitchen, there’s the coffee and pound cake, and Carolyn is talking about how Emmett Till leered at her and started to touch her, and then suddenly she comes out with, “That part’s not true.” From here, Tyson then proceeds to build a whole thesis around this idea that Carolyn falsified her testimony in 1955. And when we uncover this lie, he tells us, we lay bare the whole pathology of race relations in the 1950s South.

But Tyson himself has credibility problems. The “retraction” quote lacks proof, and the interviewee herself denies saying it. It seems Tyson brought a tape recorder along to his interviews, yet somehow failed to record the “not true” line. This is why a journalist friend of Tyson’s in Mississippi, someone who helped him with the book’s research, has openly accused Tyson of outright fabrication.

Furthermore, Carolyn Bryant Donham and her daughter put together a 100-page memoir about her childhood, the Emmett Till encounter, and all the fallout since. The key details in there are pretty much what Carolyn said in her court testimony in September 1955. As though out of spite, last month Tyson broke a confidentiality agreement with Carolyn and released her memoir to the Associated Press, apparently believing that its detailed recollections would help a grand jury indict her. But as noted in that New York Times article up top, the grand jury didn’t indict. (A PDF of the memoir is online here).

The biggest irony in all this is that Carolyn’s 1955 testimony was actually irrelevant to the outcome of the Emmett Till case. The jury never heard it. The judge sent them out of the courtroom when Carolyn came to the stand. When the jury voted to acquit Carolyn’s husband and brother-in-law, their verdict was based on evidence, not implied motive or whether or not Emmett Till used the F word. And what evidence there was, was thin and circumstantial.

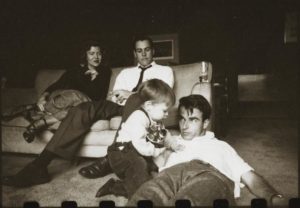

J.W. Milam, wife Juanita, Carolyn and Roy Bryant after the trial, September 1955.

Speculations and falsehoods about the Emmett Till case have plagued its press coverage since the beginning. Take for example the legend of the “wolf whistle.” In nearly every brief description of the case, one reads that Emmett Till was a little black 14-year-old boy from Chicago who was brutally murdered in Mississippi because he “wolf-whistled”—or “allegedly whistled”—at a white woman. Here is LIFE magazine’s first mention of the case in their October 3, 1955 issue:

In a sweltering small-town courtroom in the cotton-rich delta land, prosecutors for the state of Mississippi sought earnestly to convict two white men for the brutal killing of a Negro boy. (The boy, it was said, had whistled at the wife of one of the men.)

Unlike the jury, the press was present when Carolyn gave her testimony, so they knew perfectly well that the offense was not a whistle, but a physical approach with sexual overtones. Nevertheless it’s the “wolf whistle” that comes down to us in popular history. Sometimes the whistle is explained away as a bizarre speech impediment. After the trial, Till’s mother Mamie would sometimes tell people that little Bobo was maybe trying to say “bubble gum,” but was having trouble getting the words out. Meanwhile, the verbal and physical interaction in the grocery store, the overt suggestion of rape, and the fact that the husky Emmett looked like an adult and loomed over the bird-like Carolyn—these key points all get deleted from the popular telling.

The intended moral of the popular narrative is that the Deep South of the 1950s was a violent, backwards place, a region where a little black boy can be lynched for whistling at a white woman. It’s for that reason that when the recent Federal anti-lynching bill was finally passed in Congress (2021-2022), it came in under the title of the Emmett Till Antilynching Act. Federal anti-lynching bills had been introduced in Congress for a hundred years, but they never got anywhere because they were seen as superfluous—lynching after all was already illegal in every state—as well as an unnecessary intrusion into state sovereignty. Adding the Emmett Till name did the trick, though. It gave legislators an easy chance to virtue-signal, like voting to declare a National Gold Star Mother Day.

An inconvenient fact that nearly got papered over in 1955 was the fate of Louis Till, Emmett’s father. In a mawkish editorial called “In Memoriam, Emmett Till” (October 10, 1955), LIFE suggested that Louis was a war hero:

[Emmett Till] had only his life to lose, and many others have done that, including his soldier-father who was killed in France fighting for the American proposition that all men are equal.

In reality Louis Till was hanged in Italy for raping two women and murdering a third. Prior to the Army, he’d been a violent wife-beater. A judge gave him the choice of joining the Army or going to jail. After he was executed, the War Department informed Mamie Till, but Mamie chose to keep those details to herself during the media frenzy surrounding the 1955 murder trial. But they didn’t stay secret for long. By coincidence, Alabama journalist/novelist/television personality William Bradford Huie had written a book about the execution of Army deserter Private Eddie Slovik the previous year, and noticed a Louis Till grave, near Slovik’s in a special section of the Oise-Aisne American military cemetery in France. Recalling this, Huie wondered: Louis Till—could that be Emmet‘s father? Huie called up the Army’s Judge Advocate General. The JAG, after a bit of checking, told him yes indeed. Louis Till had been executed for rape and murder. (Huie discussed the matter at length in a 1979 interview.)

It wasn’t long before this spicy tidbit found its way to the editors of the Jackson (MS) Daily News, as well as Mississippi Senators James O. Eastland and John Stennis. So Eastland himself called up the JAG for confirmation, and passed the info to reporters. Soon the Jackson Daily News had a searing headline: “TILL’S DAD RAPED 2 WOMEN, MURDERED A THIRD IN ITALY.”

This revelation was more than just a curious bit of trivia. It was now mid-October 1955, and while Carolyn’s husband and brother-in-law, Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam, had been acquitted of murder, they were still in custody. They faced likely prosecution for kidnapping, which since the Lindbergh case had been a Federal crime. But the news about Louis Till put the whole story in a different light. A grand jury was empaneled to consider a kidnap charge, but they quickly came to a decision: no indictment. Case closed.

Ironically William Bradford Huie is himself responsible for some of the most colorful details—and popular misconceptions—of the Till case. He and LOOK magazine paid Bryant and Milam over $3000 for exclusive interviews, resulting in a famously lurid January 1956 article (“Shocking Story of Approved Killing in Mississippi“). Huie also interviewed some of Till’s cousins who were with him at the Bryant’s grocery store on that fateful day back in August 1955, and transcribed their first-hand observations:

Bobo bragged about his white girl. He showed the boys a picture of a white girl in his wallet; and to their jeers of disbelief, he boasted of success with her.

“You talkin’ mighty big, Bo,” one youth said. “There’s a pretty little white woman in the store. Since you know how to handle white girls, let’s see you go in and get a date with her?”

“You ain’t chicken, are yuh, Bo?” another youth taunted him.

Bobo had to fire or fall back. He entered the store, alone, stopped at the candy case. Carolyn was behind the counter; Bobo in front. He asked for two cents’ worth of bubble gum. She handed it to him. He squeezed her hand and said: “How about a date, baby?” … At the break between counters, Bobo jumped in front of her, perhaps caught her at the waist, and said: “You needn’t be afraid o’ me, Baby. I been with white girls before.”

At this point, a cousin ran in, grabbed Bobo and began pulling him out of the store.

Till’s mother later came up with an amusing explanation for that “white girl” photo. She claimed it came with the wallet when they bought it…and that girl “he boasted of success with” was actually Hollywood actress Hedy Lamarr.

Huie’s talent for hard-boiled dramatic writing comes to the fore again when J. W. Milam tells about pistol-whipping Till in a tool shed a few nights later. Bobo was standing his ground. He said, “I’m not afraid of you. I’m as good as you are. My grandmother was a white woman.”

Milam recalls his angry thoughts at that point:

“Well, what else could we do? He was hopeless. I’m no bully; I never hurt a nigger in my life. I like niggers—in their place—I know how to work ’em. But I just decided it was time a few people got put on notice. As long as I live and can do anything about it, niggers are gonna stay in their place. Niggers ain’t gonna vote where I live. If they did, they’d control the government.

“They ain’t gonna go to school with my kids. And when one gets close to mentioning flirting with a white woman, he’s tired o’ livin’. I’m likely to kill him. Me and my folks fought for this country, and we got some rights.

“I stood there in that shed and listened to that boy throw that poison at me, and I just made up my mind. ‘Chicago boy,’ I said, ‘I’m tired of ’em sending your kind down here to stir up trouble. I’m going to make an example of you—just so everybody can know how me and my folks stand.'”

This monologue is over-the-top stuff, William Bradford Huie making sure that LOOK magazine and its readers are getting their money’s worth. Huie had a good reason to overdramatize. He couldn’t tell the full story, had to be economical with the truth. He had to say Milam and Bryant killed Emmett “Bobo” Till all by themselves. Milam and Bryant were safe from further prosecution for the killing—the “double jeopardy” rule—but any accomplices they had were not. So Huie told a tale in which these two, and only these two, pistol-whipped Bobo in a shed, then drove to the riverbank, shot Bobo through the head, tied his body to a cotton-gin fan, and threw the whole works into the Tallahatchie River.

And they did have accomplices, probably at least four other individuals: two white men and two black men. In all likelihood these others did most of the beating, with one of the white men rumored to have fired the fatal .45 bullet through Till’s skull. The two blacks were Milam employees, identified as Henry Lee Loggins and Levi “Too Tight” Collins. Witnesses claim they saw these two holding Bobo down in the back of a pickup truck when he was being driven away. During the murder trial in September 1955, Collins and Loggins were sought as witnesses, but were nowhere to be found. According to the most thorough book on the case, Devery S. Anderson’s Emmet Till: The Murder that Shocked the World and Propelled the Civil Rights Movement (University Press of Mississippi, 2015), Sheriff Clarence Strider of Tallahatchie County took Loggins and Collins over to the next county and had them locked up under fake names. Reporters and prosecutors hunted for the two during the trial in September 1955, but couldn’t find them, and after the trial Loggins and Collins both denied any connection to the Till killing.

Like the possible white accomplices, Collins and Loggins are now long dead, Collins in 1962 and Loggins in 2009. Loggins did however appear in a film documentary and a 60 Minutes segment before he died (again denying any participation in the killing). Loggins was also a target of the same 2007 grand jury probe that was considering an indictment of Carolyn Bryant Donham for manslaughter. Loggins’ and Collins’ assistance in the Till murder remains an eternal blank space in the story. Their disappearance during the murder case no doubt simplified the trial immensely, as well as maybe saving their lives. But like Huie’s fictional touches, their silence leaves us with an oversimplified, often dubious narrative that’s inevitably at several removes from the truth.

We are assured the soup is delicious and nutritious and and tastes slightly different each time.

We are assured the soup is delicious and nutritious and and tastes slightly different each time.